Robert Waters Moore: doctor, botanist/horticulturist, freemason, pillar of the Anglican Church, colonial surgeon – a man with many hats.

Early Years

Born on 19 July 1819 in Cork, County Limerick, Ireland. Robert began his study of Medicine in 1837 at the South Infirmary and was apprenticed to Dr John F McEvers for five years.

However, it appears he didn’t finish his apprenticeship with Dr McEvers, but instead relocated to London in 1840. There, he worked as an Assistant Demonstrator of Anatomy at the Charing Cross Hospital for the Session 1841-1842. In August 1842, he became a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Robert continued his medical education and training at various hospitals in London, including the Westminster Ophthalmic Hospital. Finally, in 1845, he successfully earned his Doctor of Medicine degree.

Arrival in Australia

In 1846, he took on the role of medical officer on an emigrant ship, Sarah Scott, bound for Sydney. When he arrived in New South Wales, Robert worked as a medical assistant under the guidance of Mr. Benjamin Boyd of Twofold Bay.

While with Mr Boyd, Robert met Mr Oswald Brierly, the marine artist. When Prince Alfred (Duke of Edinburgh) visited South Australia in 1867, Brierly was on his staff, allowing them to renew their former friendship.

In 1847, Robert arrived in South Australia and registered with the Medical Board. He was appointed Medical Officer for the Burra Mine Company, which started operations in September 1845. The Burra mines were one of the most important industries in South Australia.

It appears that life in Burra must have been financially rewarding for Robert. An article in the South Australian Register from 17 June 1848 describes a bookcase and secretaire made by Mr. Debney of Rundle Street for Dr. Moore of Burra.

The Adelaide Times, 23 July 1849, stated on his retirement from the Burra mines that he had been earning 1500 pounds per annum, a considerable sum of money for the time.

Adelaide

After spending almost three years in Burra, Robert moved to Adelaide and established his private practice.

Initially, he stayed in a boarding house located on Rundle Street. He lodged at the boarding house with Fred Dutton, the uncle of Ludovina, whom Robert married in December 1851. Robert bought an empty plot of land next to the boarding house and built a house where he lived for the next 26 years until 1877.

His arrival in Adelaide coincided with the period of gold rush in the Victorian gold fields, which led to a significant exodus of the population from Adelaide. Despite this, unlike several other Adelaide doctors, Robert decided to stay put.

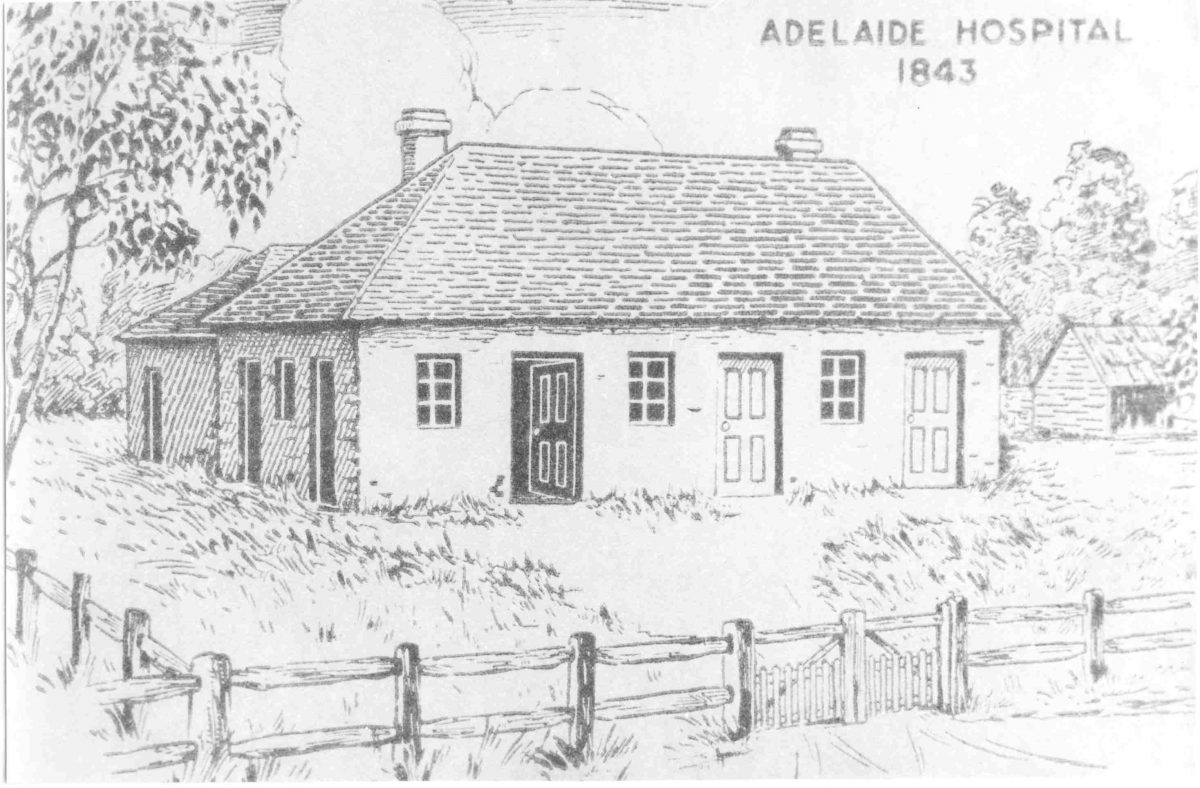

First Adelaide Hospital

The first purpose-built Adelaide Hospital opened in 1841, on the corner of Hackney Road and North Terrace. Designed to accommodate 30 patients, there were also accommodations for the dispenser and nurse. There were two wards and four smaller rooms. One room was for board meetings and operations; the second was for the private use of the surgeon’s assistant and as a dispensary. The nurse occupied the third, using the fourth as a store. The building was made of brick and whitewashed.

When Robert started working at the hospital, Johanna Briggs was the matron and in charge of the nurses, and her husband, Henry, was the hospital dispenser.

In April 1850, Robert became the first doctor in South Australia to successfully perform a caesarean at the Adelaide Hospital. The baby was born alive but died later due to prematurity.

Medical Board

In 1849, the Adelaide Hospital faced recurring financial difficulties despite being established in 1841. To ease this burden, the Colonial Secretary requested that the Medical Board allow honorary attendance by medical professionals to limit the number of free patients treated.

The Medical Board established new membership requirements stating that board members must also be consulting doctors at the Adelaide Hospital. Additionally, the six most experienced doctors in Adelaide were named honorary medical officers at Adelaide Hospital, taking turns weekly to attend to all cases.

In 1850, Dr BA Kent, one of the initial six honorary medical officers, resigned. The Medical Board suggested that Robert take the vacant position (both on the Medical Board and at the Adelaide Hospital), which the government approved. This highlights the high regard in which Robert was held in Adelaide.

Briggs Dispute

In 1852, Robert began a public dispute with Henry Briggs, Hospital Dispenser. Henry and a patient, Helen Haynes, complained against Dr Moore, who had threatened to kick Helen Haynes out of the Adelaide Hospital if she did not obey orders.

Henry’s main complaint was that Dr Moore had operated on a patient on the boardroom table. The operation was without anaesthesia and happened right next door to Johanna, who had just given birth to their child. This dispute would have disastrous consequences for Johanna in the coming years.

This also coincided with another conflict between the Colonial Surgeon, Dr James George Nash, and several Honorary Medical Officers at the Adelaide Hospital. Robert was part of this group of doctors and appears to be one of the main troublemakers.

In a letter to Captain Charles Sturt, the Colonial Secretary, Nash wrote:

I am compelled to report the determined and continued interference of a portion of the Honorary Medical Officers of the Adelaide Hospital with its internal arrangements. As these gentlemen, Mr Moore, Dr Eades, Dr Smith and Mr Phillips, have so evidently mistaken their position, I have to request that they may be informed that the executive duties of the hospital devolve entirely upon me and that I alone am responsible to HM Government, so I only must have the entire control of its domestic management.

Ian LD Forbes, From Colonial Surgeon to Health Commission, 1996

In a second follow-up letter to the Colonial Secretary, Nash accused Doctors Moore and Smith of being the instigators of trouble. He alleged that they convinced others to join them in a committee that protested against the quality of diet, medicines, and ‘other matters with which they have nothing to do’. According to Dr Nash, Dr Bayer told him that Mr. Moore’s behaviour was the sole reason for his departure from the hospital. Dr Moore had not only reprimanded the hospital staff but also spoke so harshly to the Resident Dispenser [Henry Briggs] that he cried. Ian LD Forbes, From Conlonial Surgeon to Health Commission, 1996.

The Medical Board investigated the matter and found the complaints to be valid. Dr Moore was ordered to appear before the Medical Board, but he refused to appear.

The Medical Board recorded in their minutes that Dr Moore had resigned from the Adelaide Hospital staff on 27 February 1852 and had announced his resignation to the colonial secretary but not to the Medical Board.

Colonial Surgeon

As the colony expanded, so did the duties of the Colonial surgeon. In the mid-1850s, the role of the colonial surgeon in South Australia was wide and varied. The Governor appointed the position, and his primary responsibility was to provide medical care to immigrants and the general population. Other responsibilities were:

• Superintendent of the Lunatic Asylum;

• President of the Medical Board;

• Chairperson of the Central Vaccine Board;

• Member of the Destitute Board;

• sanitation of public places;

• Superintendent of the Lunatic Asylum;

• Medical Superintendent of the Convict Stockade, located at Dry Creek;

• Surgeon of the Gaol;

• Surgeon to the serving military and their families;

• Surgeon to the Police Force;

• Board member of the Vaccination Board;

• Surgeon to the Women’s Refuge;

• Responsible for conducting autopsies;

• Supervision of hospitals and dispensaries;

• Required to attend to any public health emergencies, such as epidemics; and

• Visit the Female Immigrant Dept – he was to visit the dept twice daily in the morning and evening.

The wide range of responsibilities and duties required by one person to fulfil seems overwhelming, even in a small, newly established colony.

In 1858, Robert must have redeemed himself in the eyes of the government, as he was appointed Colonial Surgeon:

Chief Secretary to RW Moore

Philip Woodruff, Two Million South australians 1984

11th March 1858

Sir:

I have the honour to inform you that His Excellency the Governor in Chief has been pleased to appoint you to the important office of Colonial Surgeon from the 12th inst. Inclusive, and I would beg herewith to draw your attention to the number of grave and responsible duties involved in that appointment and which from your long and well-established professional character in the Colony, the Government have every confidence will be discharged by you with ability and a zealous regard for the public interests.

You will have to advise the Government in all matters affecting the public health and the sanitary condition of the colony, to exercise the entire charge and control over the public hospital to act as Superintendent of Lunatic Asylum, and medical superintendent of the convict stockade, to take medical charge of the gaol, of sick and destitute persons receiving Government aid within the city boundaries of North and South Adelaide, of the sappers and miners with their wives and families, the mounted and foot police, – to give evidence to the supreme and local courts and to attend inquests whenever called upon by the Coroner, to examine and give certificates to all candidates for admission into the Police force, also to be President of the Medical Board and central vaccine Board and members of the destitute Board. The salary as provided for in the estimates for these services in lieu of fees or other remuneration is £500 per annum with forage for a Horse, and although the Government make no express stipulation that you will abstain as Colonial Surgeon from the exercise of your private practice, yet I would state it is expected such practice would be regarded by you as altogether subsidiary to your public duties.

I have the honour to be Sir,

W Younghusband,

Chief Secretary

Second Adelaide Hospital

By the time Robert took on the Colonial Surgeon role, a second purpose-built hospital on North Terrace had been built. Opened in 1856, although only two years old, Robert inherited a building with several shortcomings. In his first year as Colonial Surgeon, Robert undertook several upgrades to address the hospital’s various inadequacies. He replaced the flooring boards in the No 2 ward due to white ant damage, purchased a lamp to assist in night surgery, installed shutters to keep out the heat of the setting sun from the western wards, and fixed the entrance to the hospital by purchasing gravel (and a cart to move the gravel) to make the driveway and road outside the hospital more accessible.

Superintendent of the Adelaide Hospital Lunatic Asylum

The first purpose-built asylum was opened in 1852 behind the original Adelaide Hospital (conner Hackney and North Terrace). The asylum comprised 18 rooms, also known as cells, and underwent an upgrade just 13 days after its inception when iron bars and shutters with bolts and locks were installed on each cell window to prevent patients from escaping. When Robert became Colonial Surgeon and subsequently Superintendent of the Lunatic Asylum, he inherited an overcrowded facility that was designed to hold 33 inmates on the female side but held 51. The male side was similarly overcrowded. Robert immediately raised concerns about the dire conditions in letters to the Chief Secretary, stating:

that such overcrowding was unhealthy, especially in the hot weather… urgent, as numbers were constantly increasing, and he would be guilty of gross cruelty were he to ignore the need.

Ian LD Forbes, Colonial Surgeon to Health Commission, 1996.

For the entire time Robert was Colonial Surgeon, overcrowding was a consistent issue. Although temporary premises and additions were built, the issue was never fully addressed due to the government’s lack of funds and support. It wasn’t until 1870 that the issue was finally addressed with the opening of the new Parkside Asylum. Unfortunately for Robert, this coincided with his retirement as a Colonial Surgeon. Dr Alexander Stewart Paterson replaced him as the person in charge of North Terrace Asylum.

During his term in office, Robert significantly changed patient management at the Asylum. He stopped the Asylum staff from using mechanical restraints and instead constructed a padded room to hold noncompliant patients temporarily. Records show that this room was seldom used while he was a Colonial Surgeon. Instead, Robert was more ‘hands-on’, giving encouragement and guidance to the patients. For example, he reported on 20 June 1858 that:

Mrs Haddock is troublesome, but with patience she can be easily managed.

Evelyn A Shlomowitz, Nurses and Attendants in SA Lunatic Asylums 1858-1884, 1994

Robert employed Moral Therapy, a 19th-century behavioural modification approach that encouraged patients to take control of their own behaviour by using therapy such as recreation and employment to reinforce good behaviour.

In charge of the Asylum, Robert was a visible presence (unlike his predecessors) and regularly supervised his staff. During his term as Colonial Surgeon, he made literacy an employment condition for both the hospital and asylum employees, meaning they had received a certain degree of education.

Royal Commission on the Management of the Lunatic Asylum

In 1864, Parliament ordered a Royal Commission on the Management of the Lunatic Asylum. The report was critical of the condition of the building and surrounding land but praised Robert and his staff’s kind treatment of the patients. Patients enjoyed good diets and were provided with beer, wine, and tobacco. Straight jackets or straps were not used, and patients were placed in a padded room to cool down.

The Commissioners stated their approval of the over-all running of the asylum and the caring conduct towards patients:

SA Advertiser, 7 July 1864

The Commissioners feel called upon to express their unqualified commendation of the general management of the institution, and of the kind treatment of the patients by the Colonial Surgeon, the Master Attendant, and the Matron, as well as by the subordinates of the establishment.

South Australian Parliamentary Committee

During the Royal Commission on the Management of the Lunatic Asylum, Robert was also under investigation for his management of the Adelaide Hospital.

In 1863, Parliament expressed concerns about the management of Adelaide Hospital and the quality of care provided to patients. This led to a report by the South Australian Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry in 1864 on the condition of the Adelaide Hospital.

The building’s condition received a lot of criticism for its run-down state, as did Matron Johanna Briggs on the state of the wards. However, the Commissioners acknowledged that Johanna lacked support from higher authorities. Robert, as Colonial Surgeon and his off-sider House Surgeon were favourably mentioned:

The evidence shows that the treatment of the patients by the medical officers has been both attentive and humane: and the Commissioners have much pleasure in calling attention to the gratifying way in which the witnesses who have been patients in the hospital have spoken both of the Colonial Surgeon and of the House Surgeon.

South Australian Register, 5 September 1964

After the report, the relationship between Robert and the Matron, Johanna Briggs deteriorated quickly. It appears she completely lost his support. Robert, in an effort to investigate her work at the hospital, initiated a Board of Enquiry, where he appointed himself as the Chair. Other Board members included the Adelaide Hosptial Medical Officer (Dr Harrison), the Postmaster-General and Police Magistrate, who quickly ruled that Johanna:

is not competent to perform the duties of Matron in a satisfactory manner, and that the efficiency of the service requires her removal.

The SA Advertiser, 12 September 1866

When she began as Matron in 1855, Johanna had a nursing staff of three with four wardsmen. When she left, there were twenty-one nurses, four night nurses and four wardsmen on the hospital staff.

The newspapers of the time showed there was turmoil over the ruling, both for and against this decision. Questions asked in Parliament and the House of Assembly argued on whether Johanna should receive compensation for her firing. The final award amount she received was 130 pounds.

1866 to 1869

In 1866, a parliamentary Select Committee again looked into the running of the hospital, and it became evident that as a Colonial Surgeon, Robert restricted outside medical practitioners from consulting in the hospital. Government officials solely managed the hospital, with no role for Honorary Medical Officers. The Committee recommended eliminating the position of Colonial Surgeon and the reinstatement of Honorary Medical Officers.

In 1868, a significant shift in the management of the hospital occurred. The responsibility for overseeing the hospital’s medical affairs was transferred to the senior house surgeon, who was to be guided by the honorary medical officers. In addition, a board of management was established to supervise all other aspects of hospital management.

Robert’s role was greatly reduced; he was left with:

- advising the government on matters of public health and sanitary conditions;

- giving evidence when necessary at the courts and coronial enquiries;

- examining medical candidates for admission to the police force; and

- serving on such bodies as the Medical Board, the Central Vaccine Board and the Destitute Board.

The House of Assembly accepted the recommendations of the 1866 Select Committee and removed the provision for the Colonial Surgeon’s salary from the 1870 budget. As a result, Robert retired from his position.

Retirement

After Robert retired in 1869, the role of colonial surgeon changed. It became an unpaid position given to the Superintendent of the Lunatic Asylum, which was finally abolished in 1913.

Robert went into private practice but continued as President of the Medical Board, an official visitor with the Lunatic Asylum and also became a consulting physician at the Adelaide Hospital in 1876

On 28 July 1876 the Adelaide Hospital Board decided to enter into the hospital rules and regulations then under review, the power to appoint as consulting surgeon, any member of the medical profession who, as colonial surgeon, had the management of the hospital, or, held the office of honorary surgeon for a period of not less than ten years. On 8 December 1876 Moore together with George Mayo and William Gosse were reported to have been gazetted as honorary consulting surgeons. Moore was the only one who did not write a letter of thanks to the board.

Bernard Nicholson, The Medical Board of South Ausralia, A Colonial Surgeon and the Adelaide Hospital – A Vignette.

Robert’s medical ability aside, it’s worth noting that he appears to be a prominent figure in Adelaide society. He was elected as the Grand Master of the Lodge of Oddfellows in 1850, the same year he joined the Medical Board. Robert also held the position of Senior Deacon of the Freemasons and was on the board of the building committee for the new Masonic Hall. He was actively involved in the Anglican Church and also on the building committee for the new Church of England in East Adelaide. Additionally, he was a member of the board and one of the examiners for St. Peter’s school. Robert’s company at these events included many influential gentlemen of the time.

Robert continued his private practice up until almost the day he died. He had been unwell for about two years before he died and, despite his family’s protest, continued to work. He died 6 December 1884 and was buried at the North Road cemetery alongside his wife. The funeral cortege was one of the longest seen up to then and included most of the prominent and important people in Adelaide.

Written by Margot Way, CALHN Health Museum

(Information sourced from Trove, Ancestry, State Library of South Australia and SA Health Museum collection. Copies of all newspaper articles and other relevant documents are available on request).