Joanna, her husband Henry and three children, arrived in South Australia in 1836 abroad the ‘Tam O’Shanter’, when she was thirty-two years old.

Born Johanna Buckley in 1805, a record fitting her description shows her charged with larceny in June 1836. She was found not guilty and acquitted of the crime. One wonders if this was the impetus for the family’s migration to Australia, as the Tam O’Shanter departed London one month later, on 20 July and arrived in South Australia, 20 November 1836.

Before emigrating to Australia, Henry’s profession was a chemist (without a medical background). Henry was born in Kent, England in 1807, although a short time before leaving England, he was working as a postman. On arrival in Adelaide, Henry registered as a labourer. This was possibly because:

free passage was often given to suitable labourers, generally men and women under 30 years of age who were healthy and of good character, expected to carry out a promise of working for wages until they had saved enough to buy land of their own.

Diane Cummings, 2017, Pioneers & Settlers Bound for South Australia 1836-1852

South Australia

When the Briggs family arrived in South Australia, it was to a newly established colony. The population of the colony was approximately 840 individuals, and there was minimal infrastructure in place. The houses were primarily constructed from salvaged materials and were quite basic. By the conclusion of 1838, the colony’s population had grown to an estimated 6,000 people.

After arriving, the family lived in Gouger Street, where Henry worked as a carpenter. It is highly likely that he assisted in the construction of houses for both present and prospective migrants. Henry was also a member and steward of the SA Philanthropic and Benefit Society. At this stage, there were no pharmacists working in the colony. One of the first was William Bickford, who opened a shop in Hindley Street in 1839 .

For the next seven years, Henry worked in various roles as a government employee. Harris and La Croix show that labourers wages between 1836-1840 steadily increased due to demand but by 1843 the average wage of labourers in building trades fell by up to 64%. Wages became stagnant and by 1846 had hardly increased at all.

Around this time, Henry applied for the dispenser’s [chemist] position (1847) at the Adelaide Hospital. To secure this position he provided references from several prominent South Australians, including Dr James Nash (Colonial Surgeon), Thomas Gilbert (Colonial storekeeper) and Robert Lowe (chemist). The change in position was probably in response to the stagnant wages and increasing unemployment. He received 100 pounds per annum, including accommodation on the hospital site for himself and his family.

First Adelaide Hospital

When the Briggs first arrived in Adelaide, there was no hospital. In fact, the first Colonial Surgeon, Dr TY Cotter, didn’t arrive until early 1837. For the next four years, the colony relied on temporary and makeshift infirmaries that were definitely not fit-for-purpose.

The first purpose-built Adelaide Hospital opened in 1841, on the corner of Hackney Road and North Terrace. Designed to accommodate 30 patients, there were also accommodation for the dispenser and two nurses. The dispenser had to be on duty 24/7 to aid patients in need of immediate assistance.

Not long after Henry became dispenser at the Adelaide Hospital, Johanna was working unpaid as a nurse in the hospital. The Colonial Surgeon, Mr JG Nash, had been unable to employ a nurse at the wages allowed by the government:

Mrs Briggs was therefore superintending the female ward gratuitously. By 1 December 1848, Nash reported that Mrs Briggs was unable to continue her services, and unless a nurse were appointed there would be none to take charge of the linen or to take care of the patients in the female ward and be responsible for their good conduct … By March 1849, Mrs McCann was appointed nurse.

Ian LD Forbes, 1996, From Colonial Surgeon to Health Commission

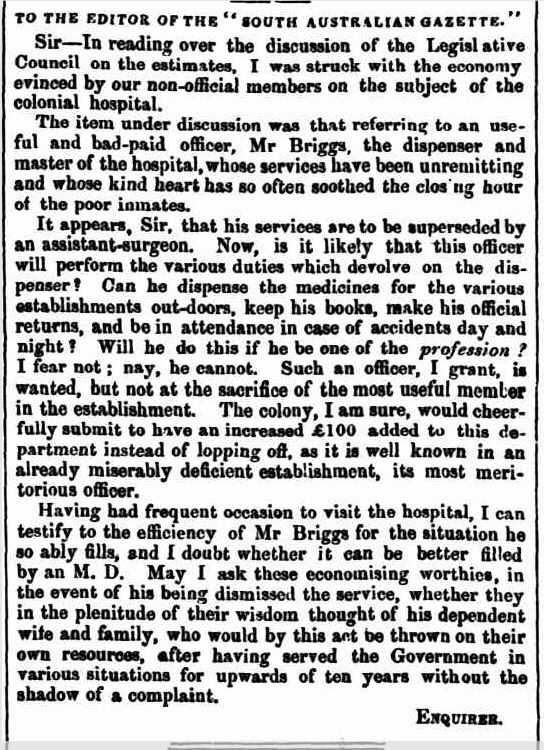

In 1849, a letter appeared in the South Australian Gazette and Mining Journal complaining about the Legislative Council estimates. The primary compliant concerned Colony estimates and whether to replace Henry’s role at the hospital by a medical doctor. The decision was clearly overturned. In the following years estimates (1850), Henry was still on the staff. He had also received a pay increase of 150 pounds per annum.

Nursing at Adelaide Hospital

By the time Johanna started working at the hospital with her husband, she had seven children and would go on to have a total of nine. Their family life was not without tragedy; four of their children died under the age of five: Edward 2 months, James 4 ½ years, George 3 months, and Lucy 2 years. George and Lucy were born while Johanna was working at the Adelaide Hospital.

As rooms were provided for the resident dispenser, Joanna was already living on-site when she began working as a nurse attendant. At the time, there existed no formal qualifications or regulations required for nurse employment. It would still be 11 years until Florence Nightingale started her nursing school at St Thomas’ Hospital and another 30 years before trained nurses started to arrive in South Australia.

Mrs McCann, the Adelaide Hospital Nurse, only stayed on staff for five months. On her leaving, the Colonial Surgeon recommended the appointment of Mrs Johanna Briggs, in her place.

Dr Nash suggested that it would be expedient to call her matron as it would give her more efficient control over the female wards, the hospital bedding and patients’ linen. The lieutenant governor’s approval was noted on 20 August 1849.”

Ian LD Forbes, 1996 , From Colonial Surgeon to Health Commission

Dr Moore Dispute

In 1852 Henry had a public dispute with Dr Robert Waters Moore that was to have disastrous consequences for his wife in the coming years. Henry and a patient, Helen Haynes, made complaints against Dr Moore, who had

threatened to kick Helen Haynes out of the Adelaide Hospital if she did not obey orders.

Bernard Nicholson, 2002, The Medical Board of SA, a Colonial Surgeon and the Adelaide Hospital – a vignette.

Henry’s main complaint was that Dr Moore had operated on a woman for piles on the boardroom table. This was without anaesthesia and happened right next door to Johanna, who had just given birth to their child. The Medical Board investigated the matter and found the complaints to be valid. Dr Moore was ordered to appear before the Medical Board but he refused to appear. The Medical Board recorded in their minutes that Dr Moore had resigned from Adelaide Hospital staff on 27 February 1852, and had announced his resignation to the colonial secretary but not to the Medical Board.

During this period, Henry placed two advertisements in Adelaide newspapers; one was for a lost bay mare and the other for a lost poley cow. It is unsure if these belonged to Henry or the hospital.

SECOND ADELAIDE HOSPITAL

Due to increasing overcrowding and unsuitability, a decision was made to construct a new Adelaide Hospital on a new location. By 1856, the hospital had shifted to the North Terrace site. Matron Johanna Briggs, was now in charge of three nurses and four wardsmen who reported to her:

NURSES:

- First Nurse: Mary Ann Martin;

- Second Nurse, Jane turner; and

- Third Nurse, Winifred Duckford.

WARDSMEN:

- First Wardsman: William Bathie;

- Second Wardsman, Henry Irehearne;

- Third Wardsman, James Prindivlle; and

- Fourth Wardsman, Joseph Kelly.

Her role as Matron consisted mainly as a housekeeper. Johanna was accountable for the well-being and behaviour of the nursing staff and to some extent the wardsmen. However, this did not include their nursing duties. This was a responsibility of the hospital doctors. Johanna’s main duties was supervising the hospital’s domestic arrangements.

A DECADE OF CONTROVERSY

The start of 1860, saw what would be almost a decade’s worth of public scrutiny of both Henry and Johanna’s work.

The controversy started when parliament members raised concerns about the religious backgrounds of nurses working at Adelaide Hospital. There were rumours that the hospital only employed Catholic nurses and would dismiss any Protestant nurses hired. However, investigations revealed that the hospital had a fair balance of both Protestant and Roman Catholic nurses, with four and five respectively. There was no evidence of religious discrimination.

Henry was also under threat of increasing his already large workload. There was a push for the dispenser of medicine to also take on the role of receiver and issuer of stores. However, parliament decided against this:

feeling that to make a surgeon’s assistant a keeper of stores would be like returning to the barber-surgeon system, under which the operations of shaving, hair-cutting, bleeding and setting broken limbs were all performed by the same practitioner.

Adelaide Observer, 4 August 1860

By 1863, Henry was now receiving 200 pounds per annum which included apartments on site, rations, fuel and light. As well as dispensing medicines for the Adelaide Hospital, he was also supplying medicine for the Gaol, the Destitute Asylum, the Lunatic Asylum and hospital outpatients.

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEE

In 1863, Parliament raised concerns about the management of Adelaide Hospital and the quality of care being provided to patients. This culminated in a report of the South Australian Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry in 1864 on the state of the Adelaide Hospital. Both Henry and Johanna received their fair share of scrutiny.

In Henry’s case, the Commissioners recognized that he had a heavy workload and found that the current created position of ‘Assistant Dispenser’ was misleading as it mainly served as a Hospital Storekeeper with little assistance to the Dispenser. To address this, the Commissioners suggested hiring a young person as a ‘pupil assistant‘ specifically to work in the dispensary.

Johanna, however, did not get off so lightly:

the wards were not so clean as they ought to have been, and that it appears in evidence that the linen and bedding are not kept in proper order. According to the rules of the institution, the matron is held responsible for these things: but, upon examination, it appears that she has not had the nurses and other subordinates under sufficient control to enable her to avoid cause of complaint; and that the implicit obedience to the matron, enjoined by the rules, has not been enforced by the higher authorities. As it is satisfactorily shown that, for a long course of years, the present matron performed her duties with great zeal and efficiency, the Commissioners are very reluctant to recommend any change”

South Australian Register, 5 September 1864

Recommendations were to employ two additional night duty nurses, and all future nurse appointments should be above the age of 25 years. The Commissioners acknowledged that Johanna lacked support from higher authorities as Matron and did not force her to resign despite her shortcomings.

Matron’s Rules

As a result of this report, the hospital Board of Management and the Colonial Surgeon (now Dr Moore), drew up rules and regulations for all hospital employees, including the Colonial Surgeon, the Matron and Nurses, through to the clerk, the washerwomen and even the lodge-keeper. Patients also had their own regulations.

Before the report was commissioned, no night duty nurses were appointed. Instead, the nurses took it in turns to sit up at night if the patient needed more intense care. The Commissioner’s recommendation of two additional night nurses assisted in relieving the overworked nurses.

Eighteen sixty-five was a bittersweet year for Henry and Johanna: in January, their eldest daughter, Mary Ann [Manford] age 30 died in the Adelaide Hospital of inflammation of the lungs. However, some good news, that in May, their only surviving daughter Ellen Henrietta, married Jenkin Coles.

DISMISSAL

Unfortunately, the situation at the hospital did not improve for Johanna. It appears she completely lost the support of the Colonial Surgeon, Dr Moore. As he was in charge of the hospital, things deteriorated quickly. Dr Moore instigated a Board of Enquiry, comprising himself, the Adelaide Hospital Medical Officer (Dr Harrison), The Postmaster-General, and the Police Magistrate, focussing specifically on Matron Briggs. They quickly ruled that Johanna

is not competent to perform the duties of Matron in a satisfactory manner, and that the efficiency of the service requires her removal.

The SA Advertiser, 12 September 1866

Dismissed from her role, Johanna was no longer Matron of the Adelaide Hospital.

When she began as Matron in 1855, Johanna had a nursing staff of three with four wardsmen. When she left, there were twenty-one nurses, four night nurses and four wardsmen on the hospital staff.

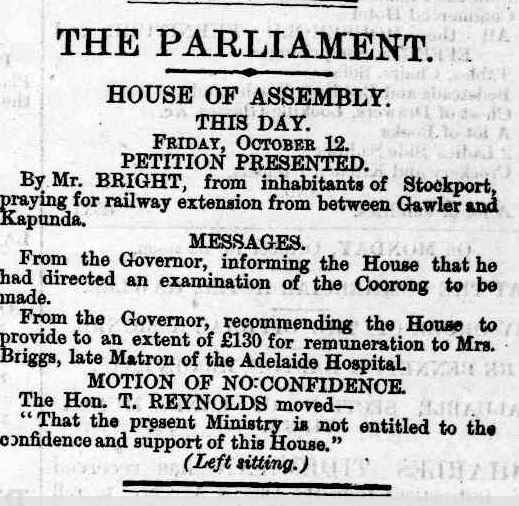

The after effects

The newspapers of the time showed there was turmoil over the ruling both for and against this decision. It must have been difficult for the family to have such a dismissal debated so publicly. Questions asked in Parliament and the House of Assembly argued on whether Johanna should receive compensation over her firing. The final award amount she received was 130 pounds.

Replacing Johanna as Matron, was Miss EF Whiteside, a current Adelaide Hospital nurse.

In the meantime, Henry was still working as the hospital’s dispenser, and the family was living onsite. This must have led to some uncomfortable moments for Johanna. Henry continued to work (and the family lived) at the Adelaide Hospital until he died in 1873. Henry suffered from dropsy (now called Oedema), which is swelling of the body due to excess fluids. For the last 7 months of his life, while residing at the hospital, he did very little work. According to the Pensions Act of 1860, Henry received nearly 468 pounds in the year 1873.

Johanna moved to ‘Home Lodge’ in Kensington, and she rented from Samuel Berry one of the two buildings on the premises. These were sizable houses of the time, situated on four acres. Here she stayed until she died in 1880. She is buried in the Catholic section of West Terrace Cemetery.

Joanna Briggs Institute for Evidence Based Nursing

Fast forward over one hundred years, and Johanna Briggs is still inspiring nurses. In 1996, a new national centre for nursing research, called the Joanna Briggs Institute for Evidence Based Nursing, was launched. Based at the Royal Adelaide Hospital, in collaboration with the University of Adelaide’s Department of Clinical Nursing, the centre was “established in recognition of the need for a collaborative approach to research and its integration into clinical practice”. Adelaidean, 2 December 1996, Vol 5 No22

It was important that the name of Joanna Briggs was attached to this new institute … We hope to honour this early Australian nursing leader and pay tribute to her pioneering efforts in the profession.

Associate Professor Kaye Challenger, Adelaidean, 2 December 1996, Vol 5 No22

Written by Margot Way, CALHN Health Museum

(Information sourced from Trove, History Trust, Ancestry, State Library of South Australia and SA Health Museum collection. Copies of all newspaper articles and other relevant documents are available on request).