Written by Dr Hamilton D’Arcy Sutherland for a talk to the Senior Dentists Association of South Australia, delivered on 12 June 1997.

My chosen topic is about the only one left to me as it is now some years since I retired from active surgical practice. The topic is by definition such a large one, spread over so many years, my cover needs to be very ‘broad brush’ and I apologise for the necessary omission of much detail which will have to be taken as read.

The surgical reality as it was before World War II has to be recognised and understood, as it was, when I was a medical student and resident at the Royal Adelaide Hospital in the late ’30s. In those years there was no thoracic surgery as such let alone cardiac surgery; the first elective cardiac operation being performed by Robert Gross in Boston in 1938.

In England – which was the base from which all surgery in Australia naturally developed – thoracic surgery was in its infancy. Major surgery in Australia was essentially general, i.e. all systems, performed by individual surgeons, working on their own carrying around a bag of instruments to wherever they were asked to go. They used general practitioner anaesthetists and general practitioner assistants. A hopelessly inefficient system by today’s standards, with little professional collaboration let alone teamwork; a situation in which thoracic surgery was not possible and if attempted, ended in high morbidity and mortality.

Surgery in the services during the war with skilled professionals living and working together started to develop the team concept especially with better anaesthesia and resuscitation and so the seed was sown.

So, after five years in the navy there I was, the senior surgical registrar at Royal Adelaide Hospital, thirty-three years old, bright eyed and bushy tailed, looking for somewhere to go.

I had D’Arcy Cowan on my back with all sorts of non-material inducements to take up Thoracic Surgery to look after his TB patients on one hand and all the senior surgeons of the day saying I would be mad to take it up because it was all honorary work and that I – along with my wife and children – would starve.

For my own part I never wanted to be a general surgeon. Thoracic Surgery seemed new and exciting, so D’Arcy Cowan won. I managed to get a Nuffield Overseas Fellowship so off I went to train as a Thoracic Surgeon at Harefield Chest Hospital London and suddenly all lights went green. I played in the hospital cricket team and there were golf courses on four sides, and I must confess my sporting success really did more to advance my position on the surgical staff than my professional skill.

Be that as it may, there I was, instantly accepted in a hospital performing major thoracic surgery, five days a week, but most all I learnt about TEAMWORK.

From the black bag surgery of Adelaide, I was transported to a 600-bed chest hospital with a 100-bed surgical unit, with Surgeons, Physicians, Nurses, Anesthetists, Pathologists, Radiologists and Physiotherapists all working in close proximity and close co-operation as a TEAM. Better still, the medical superintendent was Captain of the Cricket Team.

I returned to Australia in 1949, well trained for my age but most of all, totally committed to the ethos of teamwork, top to bottom and at all levels.

My reception back in conservative Adelaide along with my new specialty was interesting. The Surgeons right across the board welcomed me with open arms, were interested in what I was developing and referred chest cases to me from the day I got back. Even some of the most senior asked me to operate on their patients and assisted me at the operations. Doug McKay and Clarrie Rieger asked me to join the Children’s Hospital staff, as did the Repatriation Department and the Tuberculosis Service was already prepared for me by D’Arcy Cowan.

I quickly built a team around me, essentially to do the TB work but relentlessly and as expeditiously as possible I used the same team to do the non TB work which was steadily increasing.

The Physicians were a different kettle of fish with a few notable exceptions like Cowan, Sleeman, Ray Hone and Eric Gartrell who were enormously cooperative. Many physicians were frankly opposed to the new-fangled specialty as they saw it. In spite of that, things were going well, and I stuck to my guns making friends and enemies as I went, with the friends winning hands down in the long haul.

You may well ask what has all this to do with cardiac surgery? But without this solid team ethic developed for Thoracic Surgery, Cardiac Surgery would never have got off the ground.

I saw my first ten or so cardiac operations while I was still in England. Then in the early 1950s, as cardiac surgery started to develop in America and England and our cardiologists, led by Eric Gartrell, accepted the need for surgery in cardiology. They began to see patients requiring surgery and from then on, with a few successes under our belt, the Cardiologists led by Gartrell supported us 100%.

Our whole team concept was so soundly based with the full and responsible support of the Cardiologists that we in Adelaide quickly became accepted as doing the best cardiac surgery in Australia, where I believed we still are today except in one or two very highly specialised areas like transplants and neonatal cardiac surgery.

We were doing new operations every month or so – operations I had to learn out of books and journals. So, we battled on. As the field expanded, I went to England and the United States in 1955 for an intense study tour which allowed me to pick up some of the slack and see new techniques at first hand.

In the second half of the ’50s, open heart surgery began to develop especially in the United States and became a practical reality for units like ours by the late ’50s.

In 1958, we had done about 300 cardiac operations of all sorts. We were up with the field and we were doing so well with the trust and help of our Physicians and Cardiologists that they moved at a staff meeting (with our support) in May 1959 that the hospital board should be requested to make the very considerable resources available to start doing open heart surgery in Adelaide.

At that time embarking on open heart surgery was an enormous step to be taken and I have to confess that I had to give it a lot of thought. I was forty-five, which seemed old in those days, and I had slightly cold feet, but I realised there was no way out of it. I was in charge, so it had to be me!

Up to this point I have tried to show how the professional side evolved. Our success so far would not have been possible without the continuing support of the Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) administration. I had been a resident at RAH for three years and about 80% full time since returning from England, so the likes of Rollison, Brian Shea, Nicholson and Colin Rankin, who headed the administration, knew me only too well but most of all they trusted me and what I was trying to do.

So, when the open-heart proposal came up, the administration came in hook, line and sinker. Our success going through the hospital administration right up to the Premier and Cabinet reads like a fairy story compared with the bumble footed impecunious administrative stumbling of the last fifteen years.

The process went something like this. On 6 May 1959 ‘A proposal for the further development of cardiac surgery’ went to the RAH board. The real author of this document was Peter Hetzel who had just returned after several years as a part of the Mayo Clinic team who were leading the world at that time in open heart surgery. Peter Hetzel’s subsequent input in Adelaide was to put us five years ahead of the game in Australia.

Logistically we based our requirements on the current congenital heart case load and waiting list but also on the obvious developing need for valve surgery. Most prophetic of all, we submitted ‘that maybe in ten years time a greater application will be found for the heart lung machine’. Ten years later, almost to the day, we did the first coronary artery operation and ten years after that they alone grew to over 1,000 cases a year.

But I have been sidetracked. The staff submission I referred to went on 6 May 1959 to the Board and was approved by the board on 11 May. McPhie, Hetzel and I met the Board for further across the table discussion at their next meeting on 18 May. Brian Shea, the Chairman of the Board – and also of the Hospitals Department – discussed it with the Minister, Sir Lyell McEwin, on 25 May. On 28 May it went to Tom Playford as Treasurer and signed and approved by him as Premier in Cabinet on 5 June.

This meant that the whole submission was accepted as written including the budget and once that happened all systems were go.

The £50,000 we requested for the first year wasn’t questioned further, i.e. over $0.5m in today’s money.

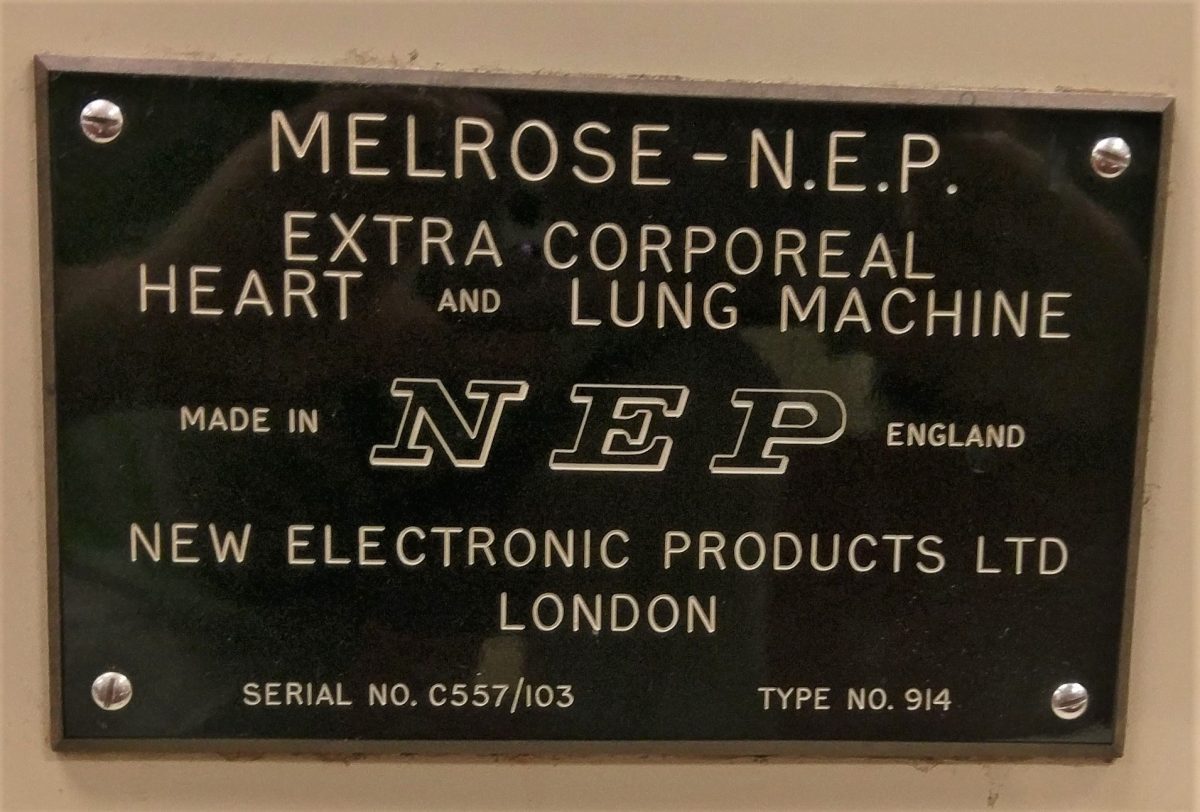

Apart from the equipment that had to be purchased, the key element was a training program which included recruiting John Waddy and sending him for six months to Hammersmith in London to learn how to run the heart-lung pump. Hetzel and I were sent to England and America for three months, other technical staff were recruited. All of which coincided with our return to Adelaide in July 1960.

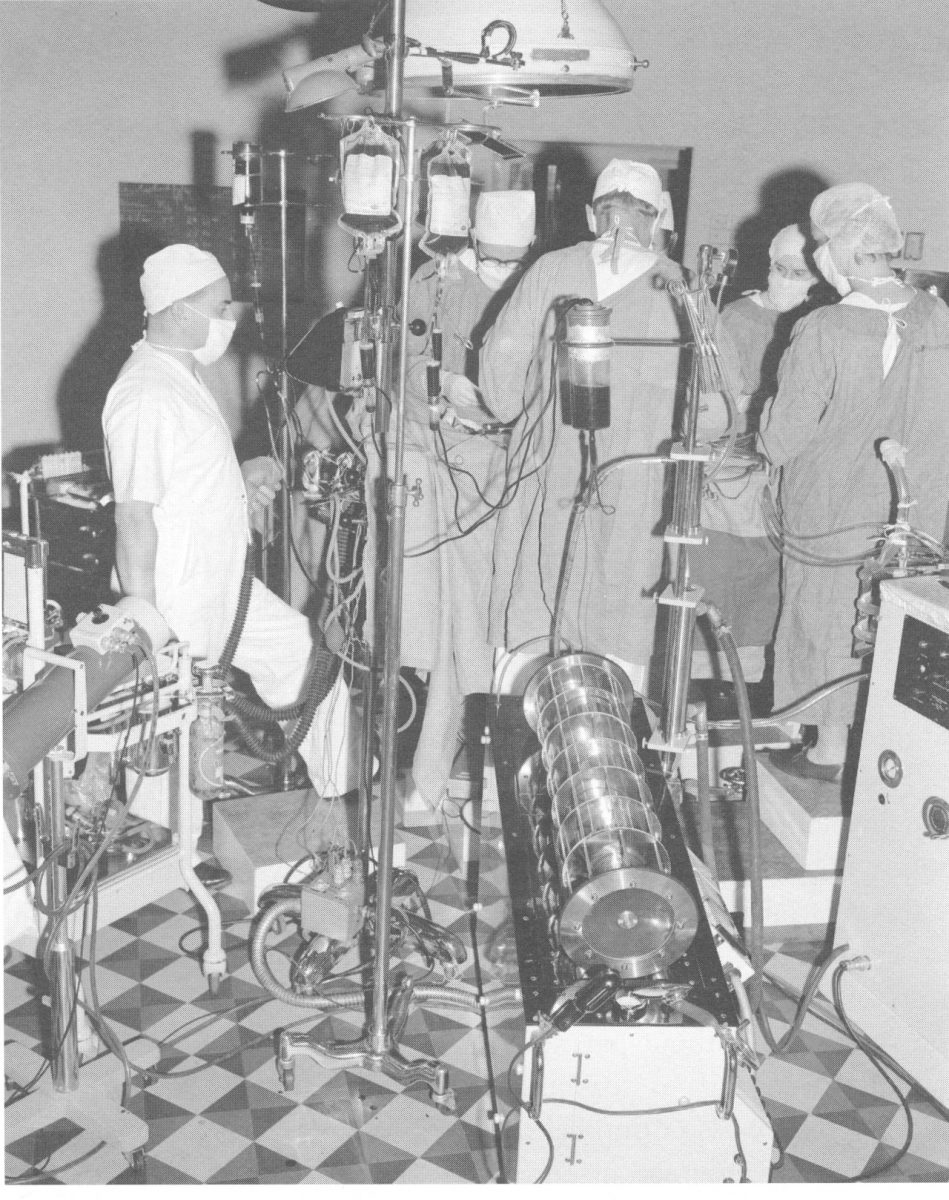

The next few months were taken up setting up the pump and monitoring, testing and calibrating the equipment. We then did ten non-survival dog experiments to get the whole team used to going on and coming off the pump.

When we were satisfied, we selected six cases to be done, one a week from 6 November 1960 come hell or high water; at the end of which time, we planned to review the whole program to decide what we were going to do in 1961.

Well, the operations were successful and all the patients survived so we were up and running and because of our solid base. The fates continued to support us at the time and the teams that followed in Adelaide, right up to today.

If I may conclude on a personal note to let you know that very recently a lady now with two adult daughters rang to thank me for her cardiac operation in 1950 which seems to say it all to me and finally, to thank you for having me to lunch.