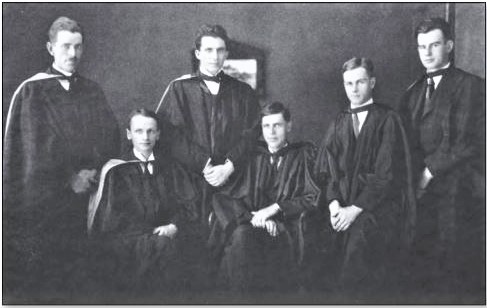

Hurtle Thomas Jack Edwards was born in Broken Hill on 26 October 1896, before moving with his family to Adelaide. On 1 January 1914, ‘Jack’ as he was always known, enrolled in the Bachelor of Dental Surgery at Adelaide University. He graduated on 14 December 1921, one of six who were the first graduates of the Dental School.

It has been suggested by other sources that Jack was a Captain in the Dental Corps during the First World War. While there is a gap in his university studies, however, no war records have been located. According to his nephew, Richard Edwards, Jack never mentioned going to war and he believes that Jack didn’t serve during WWI. He certainly didn’t leave Australia during wartime.

In 1923, HTJ Edwards and TD Campbell were the first two graduates to be awarded the Doctor of Dental Science from Adelaide University. Also, in 1923, Jack was appointed Demonstrator in Crown and Bridgework and Lecturer in Orthodontics. He was the first member of the Dental School teaching staff to concurrently hold two separate teaching commitments.

In our senior years, Dr Hurtle Jack Edwards supplemented the practical and clinical classes in prosthetic dentistry with a series of lectures which he gave seated in a corner of the lecture room, usually while smoking Craven A cigarettes. In his own account of his years as a dental student, John Lavis, describes Dr Edwards as having had ‘the best mind that I have met in dentistry

Tasman Brwon ‘Learning to be a Dentist 1946-50’

Private Practice

His private practice was in the Bank of NSW Building (corner of North and King William Streets) opposite Parliament House, where he was renowned for his laboratory. This was located at the back of his surgery where he did mainly prosthetics. Jack’s patient list was full of influential people. These included the Premier, Governor and Police Commissioner of the time, to other influential Adelaideans.

In 1956, when the Queen Elizabeth II visited South Australia, Jack was appointed the Queens dentist during her trip. Although he had no cause to treat her, he was on standby just in case.

Jack was a life-long enthusiast of cricket, a good player and was even a member of the state cricket team. From his laboratory he was able to see the Adelaide Oval scoreboard and on ‘cricket’ days would often be found standing at that window. Over a period of years, a pine tree grew up to obscure the scoreboard, much to his annoyance. So, one night after work and still in his work suit, he took a saw and cut the tree down. However, he was noticed by a local policeman but thanks to his connections, the matter soon went away.

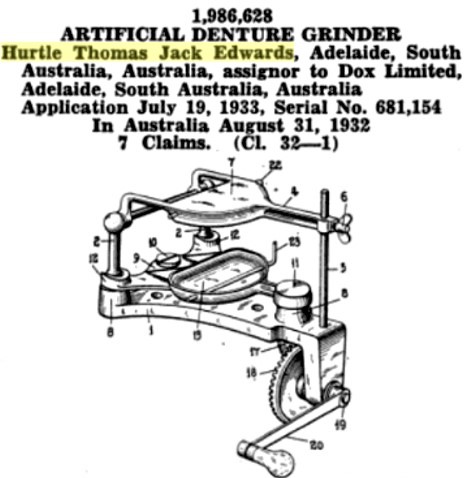

Artificial Denture Grinder

Jack invented an artificial denture grinder, called the Dox Grinder. The grinder was a hand operated machine used to ‘grind in’ the bite of full upper and lower dentures. When dentures are made, they often don’t fit together correctly and need careful grinding to make them functional. The ill-fitting dentures are attached to the machine, grinding paste is put on the chewing surfaces of the upper and lower teeth and the handle of the Dox Grinder is turned. This imitates the movement of chewing which removes any imperfections, producing a pair of dentures that fit together well.

We were mainly taught by Dr Jack Edwards and I believe we were given a sound teaching at the time. He had invented the Dox Grinder which was marvellous for giving an even occlusion when you stuffed up the bite. The FUFL was mounted on the Dox which was like an articulator with a handle. Valve grinding paste was placed between the teeth and the handle of the machine turned and the teeth would rotate against each other, remove the initial contacts and give a balanced but flat occlusion. It was the panacea for all FUFL’s with occlusal discrepancies.

Dr Myhill’s lecture ‘Dentistry in 1940’s‘

Private Life

‘Birchley’, Jack’s home, was at Vimy Ridge in the Adelaide Hills and was designed to imitate an English Hunting Lodge. The house was built with stone from the property. To get to the front door, a large rock pool moat fed by fresh water was crossed by a stone bridge. Here, Jack was able to pursue his other hobbies of metal work, where he had a large, well equipped workshop and his model train collection. His miniature train collection became so big, it took over an entire downstairs room. Richard remembers going to visit and being allowed to watch the trains but not allowed to touch. Jack did most of the work on the trains himself; it was that detailed, if you looked inside the dining car window, you would see dinner had been set with plates, cutlery etc.

When Richard was doing his master’s degree, Jack’s health began to fail. Unfortunately Jack spent quite some time in the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Richard was able to don Jack’s white coat, with ‘Edwards’ printed clearly on the pocket, and was able to freely come and go to the hospital when visiting Jack. With his health failing, Richard took over Jack’s practice and worked with him for a year before he became too ill to work. Jack thought everything Richard did was overcomplicated and too modern; he didn’t think patients should be treated horizontally and disliked the ‘high speed drills’.

Work Positions

Through out his life, Jack held many positions:

• 1923 – Lecturer at University of Adelaide (1923-34 Orthodontics, Crown & Bridge), (1929-1960 Prosthetics), (1934-44 Dental Ethics). Retired as reached the age limit;

• 1924-1925 – President State Dental Society;

• 1924-1948 – Honorary Dental Surgeon, Royal Adelaide Hospital;

• 1924-1951 – Member of the faculty of the Dental School;

• 1927 – President of Australian Dental Association of South Australia for three terms of office;

• 1933 – Federal President and President of the Australian Dental Congress; and

• 1945 – Awarded Companion of the order of St Michael & St George for services to dental profession in South Australia.

Jack died on 25 September 1973 at the age of 76.

Written by Margot Way, CALHN Health Museum