Peter Stuart Hetzel, Emeritus Cardiologist, Royal Adelaide Hospital

This address was delivered at the fourth Foundation Day Ceremony held at Royal Adelaide Hospital on 14 July, 1982. The occasion included the dedication of the stained glass window The Good Samaritan by Cedar Prest.

‘Nurses are dull, unobservant and untaught.’ ‘Nursing is generally done by those who are too old, too weak, too drunken, too dirty, too stolid or too bad to do anything else.’

Of these two generalisations the second was from Florence Nightingale, perhaps overstating her case for the need for nursing education and the first said by Sir James Paget of Paget’s Disease fame from his position on the staff of St Bartholomew’s Hospital in the 1830s.

Let me add a quotation recorded by the Ashley Mines Commission in England in 1842:

I am Sarah Gooder. I am eight years old. I’m a coal carrier in the Gawber Mine. It does not tire me, but I hate to trap without a light and I’m scared. I go at four and sometimes half past three in the morning and come out at five and half past in the evening. I never go to sleep. Sometimes I sing when I’ve light but not in the dark; I dare not sing then. I don’t like being in the pit.

I am very sleepy when I go in the morning. I go to Sunday School and learn to read. They teach me to pray. I have heard tell of Jesus many a time. I don’t know why he came on earth. I don’t know why he died, but he had stones for his head to rest on.

This child spoke in England but one could not believe that the level of education and the experience of life of those who were unskilled immigrants in South Australia in 1840 and 1841 was any better. Of such would have been those who sought treatment in this hospital when it opened its doors in 1841; with care given by nurses perhaps of the calibre and general quality described by Miss Nightingale and Sir James Paget.

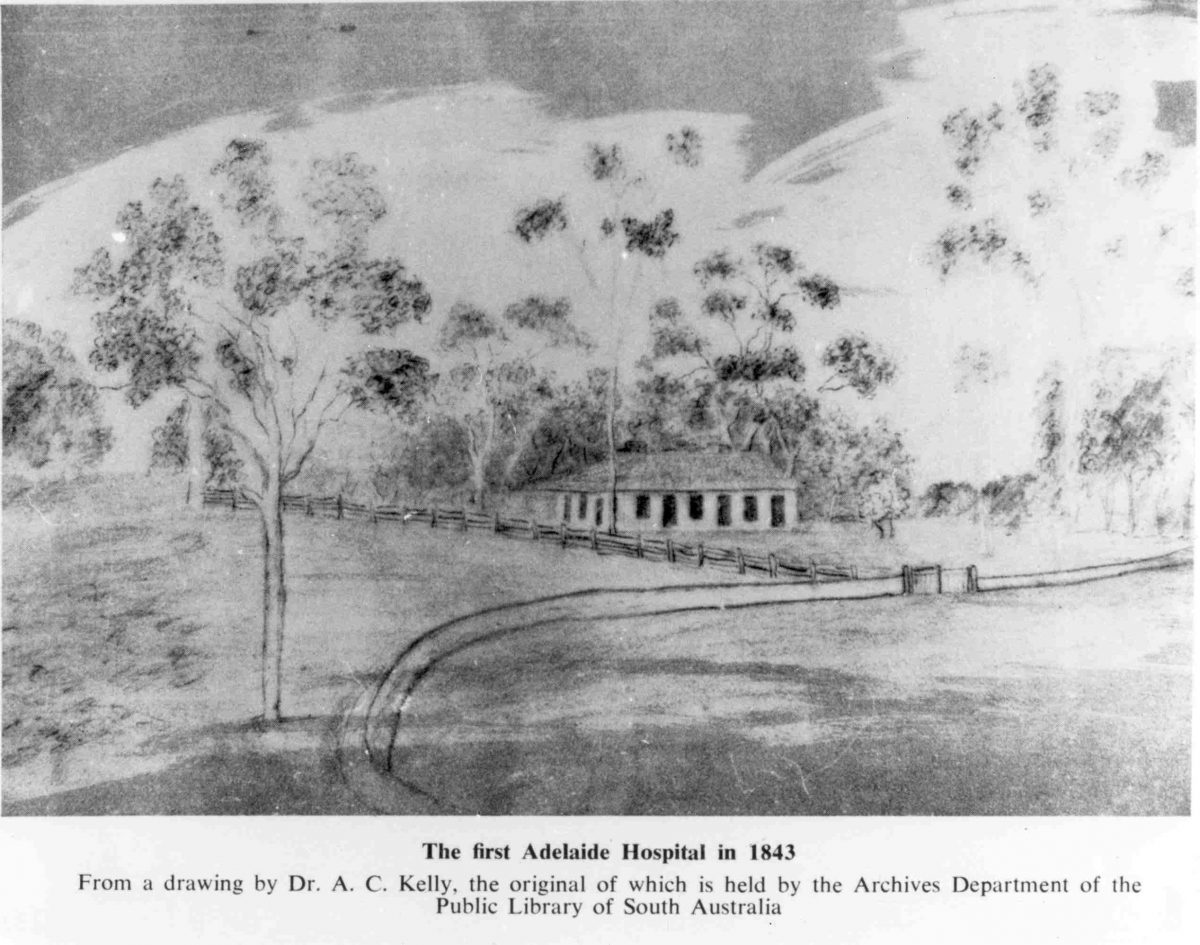

Today we commemorate the laying of the Foundation Stone by Governor Gawler in 1840. He was recalled before he could see the hospital completed. He had followed a policy in a period of economic stagnation in the private sector by increasing expenditure in the public sector, to help employment. This is a policy which we would acknowledge today as having its own strong advocates in our present economic difficulties. Whatever may be present solutions, we have reasons to be thankful that Gawler acted as he did.

In his history of the hospital Mr J Estcourt Hughes has laid before us a fascinating account of the development of the hospital from its beginnings. I would like to reflect a little longer on the situation in 1841 when it opened its doors. In the city there were the gentry – many speculating madly in land, the skilled workers and the unskilled. I do not imagine that the gentry and the artisans would have chosen to be admitted to the hospital. They were not keen in the 1940s – a hundred years later. Such people would have been tended by their womenfolk in the way that women, particularly gentlewomen, had been associated with nursing for thousands of years.

For the poorer people there would have been no alternative when sickness was severe or an accident occurred. The medical staff would have visited the hospital, diagnosed, advised, operated and prescribed, but, as always, it would have been the nurses who did the work – the nursing, the cleaning, the preparation of the food, the care of the sick. It is easy now 140 years later to be critical of those who may have been almost as bad as Miss Nightingale has said. For all we know in 100 years’ time, people may have similar accounts about our own management.

Effective training of nurses in this hospital began in the 1880s and the medical school admitted its first clinical students to the wards in 1887. Miss Nightingale started her school in 1860, Lister published his first paper on antiseptic care of fractures in 1867. The work of Pasteur was to follow and in due course all these developments and more came to be applied in the hospital.

Now clearly the application of all the developments in nursing and medical education, all the discoveries of medical science, all the contributions of social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and others are very important to the conduct of the hospital and as important in many ways as has become the development of hospital administration to enable the hospital to function properly. These aspects are important but there are a number of other things that have happened which are also vital.

Firstly on a number of occasions this hospital has had to undergo a process of renewal. The famous hospital row required change, modification and finally reconciliation. At various times there have been struggles between the board and the staff. In the 1960s it was a physical renewal which produced a completely new hospital. However much we liked the buildings and traditions of the old hospital I consider we need to be very thankful for the new. Another process of renewal has been in the altered conditions under which some of the medical staff work. The honorary system has gone but for many the attitude of service for something different from money remains and it is not limited to the older medical staff or the medical staff at all for that matter. It has existed behind the service of most other staff members anyway.

This process of renewal is essential if the hospital is to have any future. It must recognise its role in the community and it must be prepared to argue its case for an appropriate role. In many large cities we have seen central hospitals close down or shrink because they are no longer in a position to serve. Sometimes this is because the people have moved away and others it is because the hospital has become a non-viable financial enterprise. This means that we have to have our own understanding of our purposes in Adelaide in the 1980s and the 1990s and be prepared to defend that view, if it is defensible.

In speaking of the hospital as an institution we tend to give it a separate identity, a single identity, and of course this is false. It depends totally on the people who work in it. We set standards of care, we are responsible for morale. We can be under threat over money, over staffing levels, over equipment crises and pious words will not resolve these things. We each in many ways have to learn to contribute to the solutions and this demands not only our loyalty but a sense of purpose and a high level of morale and of course, we all stand in danger of believing all the things that the press, the public and even the government say about us. All unreliable. We have to be realistic about our deficiencies as well as our successes. It is easy to be arrogant and believe that the hospital has a life of its own. As long as those who work in it have an approach of hope about its failures and humility about its successes we will not delude ourselves too much.

But again I have tended to speak about the hospital as different from the people who work in it.

If the place is worth anything at all it must be because people enjoy working in it, because the work is worthwhile, because the relationships with others are worthwhile and because those whom we seek to help make it appear worthwhile as well. In all this there is one quality above all without which the place does not deserve to exist. It has nothing to do with foundation stones or education or medical discovery or old buildings or budgets or manpower budgets or frozen food or linen shortages or parking – it is all put together in the one word – compassion. Yes, the compassion of the Good Samaritan. The nursing staff has always been the prime example of compassion and the doctors to a limited degree. Many other staff may not appear to have the opportunity to be compassionate but anyone who comes into contact with the public has the opportunity to demonstrate compassion. There is nothing wrong with being compassionate with others in the work place no matter where we work.

The willingness of the Samaritan to offer succour and all the support he could to the stranger has always stood before us. Some will use the word pity and that is what the Bible says and certainly Christ is often translated with the word love. Our language is limited in the words it has to describe this particular emotion. I believe compassion is the appropriate word.

For some, dealing with people can be very difficult. They feel shy, embarrassed, inadequate. They may be nurses, doctors, physiotherapists, social workers, laboratory technicians or wardsmaids. It may be difficult to approach people. Those who need help in a sense approach us. If we can see or hear them we can see their need and their need provides the avenue for the approach to give.

The public tends to idealise the work of doctors and nurses. Certainly we are fortunate and privileged to be needed, for let’s face it, it is good to be wanted. If the patients did not require us we would certainly feel futile. Not that we have to pray for patients to keep coming to the hospital. That will happen as long as the hospital is here but now it happens because the hospital is here, because it not only administers first class medical attention and no-one any longer has reservations about care, but because also, and as importantly, the staff is good. They cannot be good without compassion.

Compassion is not just a feeling – the Good Samaritan acted as well – and so being compassionate means not only being supportive but being skilled in treating as well and doing something. So that as we look forward from our beginnings we acknowledge the compassion of those who have worked before us and work here now. We see commitment.

To conclude let me give you two other quotations. The first is from a modern writer, John Gardner, a former Secretary of Health Education and Welfare in the United States Government in the 1960s:

We hold in our hands the tools to build the kind of society our forebears could only dream of.

We can lengthen the lifespan as they could not. We can feed our children better and educate them better. We can communicate better amongst ourselves and with all the world.

We have the technology and the means of advancing technology. We have the intellectual talent and the institutions to develop it and liberate it. We can build the systems and organisations, public and private, to which our common goals can be pursued.

We have these things not because we are any smarter than those who came before us but because we can build cumulatively on their creative efforts and achievements.

Far less than any other generation in the history of man are we the pawns of nature, of circumstance, and of uncontrollable forces – unless we make ourselves so. We built this complex, dynamic society and we can make it serve our purposes. … If we can build organisations we can make them serve the individual.

To do this takes a commitment of mind and heart, as it always did. If we make that commitment, this society, (this hospital), will more and more come to be what it was always meant to be: a fit place for the human being to grow and flourish.

And so finally, let us remember the commitment of Ignatius Loyola:

Help us Good Lord

To serve Thee as thou deservest,

To give and not to count the cost,

To fight and not to heed the wounds,

To toil and not to seek for rest,

To labour and not to ask for any reward,

Save that of knowing that we do Thy Will.