Presented by Dr Peter S Hetzel AM, Emeritus Cardiologist, Royal Adelaide Hospital

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton wrote those words in a letter to his friend Robert Hook in 1675.

I have chosen three giants and one giantess to exemplify the contributions they made to the development of this magnificent institution. In case you are concerned about the existence of giantesses, I can tell you that in the time of Middle English in the Fourteenth Century, giantesses were described – even if in this still male-dominated world they are not recognised. I hope it is because the term giant is considered now to include both sexes.

So the giants are:

William Wyatt, Margaret Graham, Henry Simpson Newland and Constantine Trent Champion de Crespigny.

There are other giants in medicine who as students trained in this hospital. They include Florey and Cairns, who achieved greatness working overseas. Others such as Fenner and Warren also received their initial training in Adelaide and achieved prominence working elsewhere in Australia.

Others have been recognised for their achievement working in this hospital – particularly post WWII. Most have died in the past 20 to 30 years. They will be recognised as having been giants in their own time.

William Wyatt arrived at Holdfast Bay with his wife, Julia, on the 11th of February 1837 aboard the “John Renwick” which sailed from Gravesend on the Thames in London on the tenth of October 1836. He was the ship’s surgeon. His medical qualifications were Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries – a qualification for general practitioners. He was also a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons of England – a specialist qualification for a surgeon. He had been in practice in Plymouth – his hometown – for 8 years. We do not know the source of his intention to migrate. He had been introduced to George Fife Angus “with the recommendation of having many honourable qualities, a keen supporter of the Literary Institute and public museum. Aged 31 he was said to be studious, prudent, industrious, honourable, strictly moral and well-disposed to religion, having had the advantage of pious parents.”

Shortly after he arrived the decision was taken to accept Light’s proposal for the site of the city of Adelaide. With this decision taken, land auctions were held and Wyatt purchased two acres between Grenfell and Pirie Streets, paying £20 for each. It is noteworthy that in the following year half an acre was sold for £755.

It is recorded by Carol Fort who has published a wonderfully detailed biography, that having been in Adelaide for 6-7 weeks he had attended political meetings, performed medical and religious duties, bought 6 acres of townland and built a hut with his own hands.

From the very beginning, Wyatt was involved in the affairs and conduct of the hospital. In 1841 he was appointed an Honorary Surgeon – only to resign with his colleagues over the conduct of another surgeon. He became concerned over the alleged qualifications of some who claimed to be medical practitioners. In 1844 a Medical Board was established which he served as Secretary until his death. Over the years there were several enquiries about the conduct of the hospital. One such enquiry related to allegations that some persons were claiming to be poor, so that they could avoid paying the weekly 21 shillings required. A new Board of Management was established with Wyatt as Chairman until his death in 1886.

Wyatt’s interest and concern for the Aboriginal people was shown very soon after his arrival, being appointed Protector. In May 1839 with the arrival of Governor Gawler he was able to translate the Governor’s speech into the Kaurna language. Some months later when the many new arrivals were taking over land there were difficulties which he had to resolve. Finally he had to resign, but his concern and respect continued. In 1879 he contributed a chapter “Some Account of the Manners and Superstitions of the Adelaide and Encounter Bay Aboriginal Tribes” to a book entitled “The Native Tribes of South Australia”, published by E. S. Wigg and Son.

He filled many public roles – coroner, magistrate, justice of the peace, inspector of schools, one of the founding fathers of Pulteney Grammar School and St Peter’s College. He was active in the affairs of the Church of England as it was then known. He was a farmer (Kurralta Park) and had extensive landholdings. He had major scientific interests which led him to be the Honorary Naturalist and he worked to establish the Botanic Gardens.

With no surviving children and able to provide well for his wife, in 1881 he established the Wyatt Benevolent Institute with about £50,000. Its purpose was to “benefit persons above the labouring class who may be in poor or reduced circumstances.” Some may consider that the money should have been given to the needy of the labouring class but Wyatt was a creature of his time. It was not until the early 20th Century that Britain, following a New Zealand example, introduced the aged pensions. The Benevolent Institute has functioned since that time. It is governed by a Board of seven Honorary Trustees. In the 2004-05 financial year over 1 million dollars was awarded in grants.

Was Wyatt a giant? I consider he was. Shortly after his arrival the Adelaide Hospital was established. We do not know whether following his resignation he returned to surgical duties in the hospital. We do know that he was responsible for the Medical Board. After 1867 he was Chairman of the Hospital Board. He was certainly a giant of education – both public and private. With his scientific interests and his work seeking to understand Aboriginal culture and the established Wyatt Benevolent Institution he should certainly be considered a giant in those fields. Wyatt died on 10 June 1886 in Adelaide.

Margaret Graham was born in Carlisle, in Northern England in 1860. She was Matron of this hospital from 1898-1920. She had come to Adelaide in 1891 and shortly after enrolled as a probationary nurse. On completion of her training she was recommended for appointment as a charge nurse. However, other matters were happening. A vacancy in the Matron’s position occurred. This was filled by promoting the senior night sister. With a vacancy for this position the Hospital Board appointed Miss Hannah Gordon, overlooking a number of more senior nurses. The problem was that she was the sister of the Chief Secretary who was the Minister responsible for the hospital. A number of nurses including Miss Graham wrote a letter of protest to the Board. The Board considered the nurses to be disrespectful and impertinent and demanded an apology. All but nurses Graham and Hawkins complied. Those two were suspended from duty. The matter proceeded to arouse ire. The premier became involved, the matter was raised in the press and Miss Graham wrote a letter critical of the Board. Having been suspended, she undoubtedly felt she had nothing to lose. A Royal Commission was established which found Miss Graham’s charges were not supported but considered that the nurses had been justified in protesting. The Board refused to re-install Miss Graham and her colleague. The Government insisted on re-installing and indicated it was sacking the Board. The Medical Superintendent, the Matron and Miss Gordon resigned in support of the Board. However, with the prospect of Miss Graham being reappointed by the Premier, the whole of the Honorary staff resigned.

This had very serious implications for the medical students in the middle of their clinical training. They had to go elsewhere to Sydney or Melbourne as these were the only other medical schools in the country. As a result of transferring and then completing their training elsewhere most never returned to Adelaide. It was not until 1901 that clinical teaching was resumed. In 1891, Miss Graham was appointed night sister and then when the vacancy arose in 1898, Matron. She was the only applicant for the position of Matron.

As Dr Joan Durdin points out in her estimable biography of Miss Graham, those first years of her appointment were difficult. It would appear that she had no say in nurse appointments, these being made by the Board. She was able to object then, having to justify her particular objections to the Board.

Miss Graham took up activities in the interests of nursing. In Britain, nursing leaders were becoming concerned about standards of practice. The Royal British Nursing Association had been established in the 1880s. In 1900 Margaret Graham was invited to establish a branch in South Australia. This she did, serving as its lady con-sul until 1920. After some years she was also active in the Australian Trained Nurses Association.

With Federation in 1901 the National Government established an Army Nursing Reserve. Miss Graham was appointed the first lady Superintendent in South Australia. With former Adelaide Hospital nurses joining the reserve, training was given in various aspects of military practice – hygiene, military organisation and military surgery. On the outbreak of WWI Miss Graham took leave and enlisted in the Australian Army Nursing Service. She embarked from Melbourne in December 1914 and served in the Middle East and on hospital ships evacuating the wounded from Gallipoli. She received The Order of the Royal Red Cross First Class in December 1916.

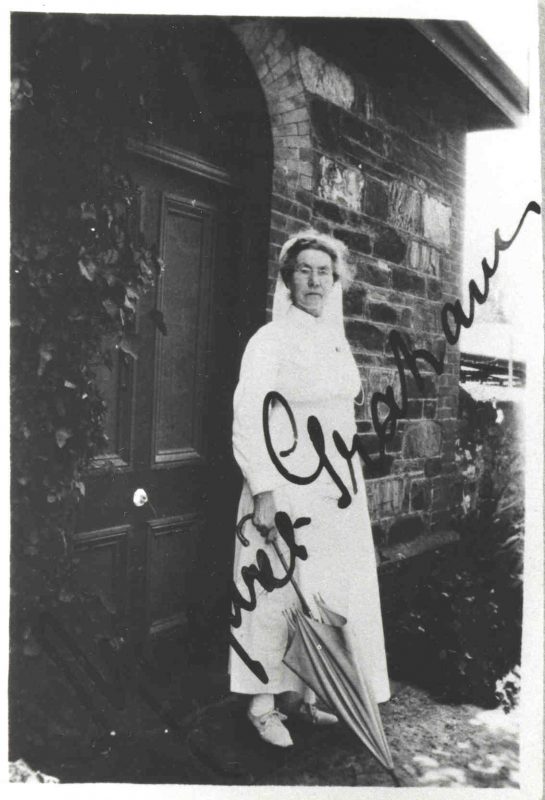

When Miss Graham returned to her position at the Adelaide Hospital in August 1918, the city was in the grips of the world wide influenza epidemic. In January 1919 she was transferred temporarily to be Matron of the emergency hospital set up in the Exhibition Building on North Terrace. When the epidemic was over she returned to her role as Matron. Six months later, in 1920 at the age of 60, she tended her resignation and returned to Carlisle. More than three thousand nurses were trained in the hospital in her time. A photograph shows of the Guard of Honour when she left the hospital. Back in England she was often visited by nurses who had trained at the Adelaide Hospital. She died in 1942 acknowledged as a disciplinarian but strictly fair, highly respected and much loved.

The nurses’ home building from 1908 was named the Margaret Graham Building in 1955. She would have known that when the building was coming to completion the architects had forgotten to allow for toilets.

“Margaret Graham had taken an early stand against injustice in the workforce. She bore the consequences for the rest of her nursing career. She worked in an environment in which compliance and acceptance of a subservient role was considered the norm for women.”

Dr Joan Durdin

Clearly she was a giant.

Henry Simpson Newland was born in the family home in High Street, Kensington on the 24th of November 1873. His grandfather, a congregational minister, had migrated with his family in 1839 and had settled in Encounter Bay. Henry’s father was born in Staffordshire in 1835 and has been described as a pastoralist, author and politician. Henry was the eldest of 5 sons. He attended St Peter’s College and entered the Medical School of the University of Adelaide in 1892, graduating in 1896 sharing top place. This was the time of the Hospital Row, so he could not receive the usual clinical training of a Resident Medical Officer.

Wishing to pursue a surgical career he left for England in January 1897, hoping to get a position at the London Hospital. But these positions were all allocated to those who had received their clinical training in the hospital Medical School. To overcome this difficulty Newland enrolled as a student. After 6 months he gained the conjoint qualification – Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians (London) and Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Completing the year he hoped to work under Mr Frederick Treves, the foremost surgeon of the London Hospital. In his biography of Newland, Estcourt Hughes says that when he was told that the hospital appointments committee looked favourably on those who rowed. Having rowed at school and at University, this was no problem. He joined the hospital rowing club and was able to row in the hospital team on the Thames.

He gained a position as Resident Medical Officer at the Hospital, but Treves had left for the South African War. Newland was successful in passing part 1 of the examination for Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons and passed the final examination in May 1899 at his second attempt. In due course he gained the appointment of Surgical Registrar – the only one at the London Hospital with a thousand beds. He had spent a period at Great Ormond Street – the Hospital for Sick Children and maintained his interest when later he gained an appointment at the Adelaide Children’s Hospital. There was the likelihood of him gaining an appointment as surgeon at the London Hospital but there would be no vacancy for years. Accordingly, Newland returned to Adelaide in 1902. He joined Dr Henry Marten in his practice and was appointed assistant surgeon at the Children’s Hospital. In 1908 he undertook a study tour to England, Paris and then the United States. On his return he was appointed Honorary Assistant Surgeon at the Adelaide Hospital.

When the First World War broke out in August 1914 Newland enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force. His unit was the First Australian Stationary Hospital. Having left Melbourne the unit arrived in suburban Cairo. In January 1915, Newland along with his colleagues Henry Powell and Stanley Verco were deployed to Ismailia when the Turks attacked the Suez Canal. The hospital later moved to Lemnos. When established it had 400 beds but this was expanded to 1000. In May 1915 the staff of the No 1 Australian Stationary Hospital was sent briefly to Helles. Returning to Mudros the Hospital was very busy treating 3,951 sick and wounded in the first 3 months. The unit then returned to Egypt in December 1916. Newland was posted to the First Australian Casualty Clearing Station as Commanding Officer. In March 1916 the unit proceeded to France and was set up at Estaires and remained there for 13 months. In March 1917 he was posted to the Third Australian Casualty Clearing Station as specialist Surgeon. Initially this was at Dernancourt on the Somme and then moved for the third battle of Ypres.

In December 1917 he was sent to the Australian Section at Queen Mary Hospital at Sidcup in Kent, which had been set up for treatment of facial injuries.

This hospital had British, Canadian, New Zealand and Australian sections, serving the wounded troops. There was a preliminary period of observing the techniques evolved by the British. Newland performed his first procedure in January 1918 and remained there until the middle of 1919. A picture shows the senior staff at Queen Mary Hospital with Queen Alexandra, the widow of King Edward VII. Newland gained his skills and successfully applied them to plastic surgery – gaining renown for his success. He had been awarded the D.S.O. in 1917 and in 1919 was created a Commander in the Order of the British Empire.

Returning home he resumed his surgical practice and teaching. Highly skilled, he was appointed a Senior Surgeon in 1919 having been away for four and a half years.

He played a major role in the activities of the British Medical Association and in the creation of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons in 1927. He served as its President from 1929 to 1935.

In 1950 the Royal College of Surgeons celebrated its sesquicentenary – 150 years. Newland (Sir Henry since 1928) attended and presented an address from the Australasian College. As a young Fellow he had attended the Centenary dinner in 1900. By 1950 he was the only survivor of that occasion.

There is much to tell of Sir Henry Simpson Newland. He was certainly one of the most highly skilled surgeons in Australia. He retired from the hospital in 1933 at the age of 60 but continued to practice. Dr Estcourt Hughes’ very readable biography tells it all.

Sir Henry Simpson Newland died in November 1969, eleven days before his 96th birthday.

Our fourth giant is Sir Constantine Trent Champion de Crespigny, generally referred to by his juniors as “Crep”. A painting shows him arrayed in the glory of the gown of the Melbourne University M.D. Doctor of Medicine. Among many accomplishments he was the founding father of the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science. Though the name has been removed by legislation the building stands as his memorial, though extended considerably since he would have last seen it in 1952.

Born in March 1882 at Queenscliff in Victoria he attended the Medical School at the University of Melbourne graduating in 1903. His forebears were not Huguenots. They came from Normandy and could proudly trace their lineage to the time of William the Conqueror. Following graduation he had various positions in Victoria. His career in Adelaide began in 1909 when he became Medical Superintendent of this hospital. He was 27 and held that position until 1912. In those years hospital laboratories were mainly concerned with bacteriology. In Adelaide in 1899 a bacteriological department was formed at the Adelaide Children’s Hospital as an institute of hygiene and bacteriology with Dr Thomas Borthwick as Honorary Director. In 1902 Borthwick was appointed Honorary Bacteriologist to the Adelaide Hospital. Within a year of his appointment as Superintendent, Dr de Crespigny had prepared a report about pathology services and the need for development in what was called Clinical Pathology. He set up such a laboratory in a disused shed behind the hospital in 1911. The Registrar of the University of Adelaide wrote to the Hospital Board concerning the intention of the Board to establish an Institute of Pathology with Dr de Crespigny, requesting that these facilities be available to medical students. The Board also sought agreement to the appointment of Dr de Crespigny as University Lecturer in Practical Pathology and Histology. De Crespigny resigned from his position of Medical Superintendent, continuing his teaching appointment at the University. He was appointed Honorary Assistant Physician and went into private practice as a Physician. From 1912 to 1919 he held the post of lecturer in Pathology at the University.

De Crespigny had been commissioned in the Medical Corps in 1907 and posted to the Light Horse Field Ambulance as a Captain. After the outbreak of World War I he was called up for active service and in May 1915 he left Australia and was posted to the Third Army General Hospital. He reached Mudros on Lemnos in August, first as Second in Command with a rank of Lt. Colonel. He was then placed in command of the First Army General Hospital taking the unit to Rouen in France. In June 1917 he was awarded the D.S.O. A picture of de Crespigny walking with Queen Mary was taken in July 1917. From August 1918 de Crespigny served as Consultant Physician to the AIF in London until April 1919. Before returning to Adelaide he successfully passed the examination for membership of the Royal College of Physicians (London), becoming a Fellow in 1929.

Back in Adelaide he resumed his role at both the Adelaide Hospital and the Children’s Hospital. His appointment at the Adelaide Hospital continued until 1942. With the appointment of J. B. Cleland as Marks Professor of Pathology in 1920 he relinquished his lectureship role in that field. As a teacher in Pathology he had had a major influence in the teaching of medical students but as a Lecturer in Clinical Medicine and Practice his influence was even greater. Dr Estcourt Hughes, who graduated in 1926, had experienced de Crespigny’s teaching He wrote in his history of the hospital:

“as a clinical teacher his outstanding characteristics were an insistence on a thorough examination and his painstaking instruction in the eliciting of physical signs and their interpretation. His systematic lectures were of a high order, with emphasis on concentrating on the clinical manifestations of disease and its pathological basis”.

Dr Estcourt Hughes

He like Newland played a role in the organisation of Medicine. He also like Newland had a period as President of the South Australian Branch of the BMA and played a significant role in the founding of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians in 1938, serving as President from 1942 to 1944. He was knighted in 1941. He served as Dean of the Medical School for 19 years.

However, with all these activities it must be recognised that his work, leading to the creation of the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science, was that of a giant. This institution, serving the public, the hospitals both public and private must be considered his major achievement. He served as Chairman of its council from its beginning from 1938 until a few months before his death in October 1952.

With his passing there were many tributes. One account described him as being tall with a spare figure, always immaculately dressed, inspiring awe in students who knew of his uncompromising scorn of slipshod work. His teaching, thorough and with a basis of pathology was always lucid and logical but lightened by a dry humour. Others described him as the outstanding clinical teacher of his day.

In closing I must pay tribute to Carol Fort, Joan Durdin, the late James Estcourt Hughes and the late Bernard Nicholson, each of whom had the vision to provide biographical accounts of these giants from which I have drawn heavily.

Additionally I wish to acknowledge the skilled assistance I have received from the staff of the Heritage Office.

The one woman and three men I have referred to as giants for their contributions to this hospital have left it to succeeding generations to have the visions to make their contributions to the work of Royal Adelaide Hospital. In acknowledging its heritage, they will carry it forward to a new site.