Written and read by Ray Liddle at Neville Martin’s funeral – 14 April 2022

In September 1957, Neville’s background in radio and television broadcasting matched him perfectly for the position of “Cardiological Technician” at the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

He commenced duties at Royal Adelaide Hospital Cardiac Clinic under the guidance of the Honorary Cardiologists Dr Eric Gatrell and Dr John McPhie. Neville was tutored in the mysteries of ECG recording and waveforms.

The Cardiac Clinic had recently been equipped with the Adelaide-made Both ECG machines. Maintenance of these ink pen devices was a very messy job.

In 1960, following a proposal to the Department of Health by Dr Peter Hetzel and Mr D’Arcy Sutherland to develop Cardiac Surgery as a State Service, the Cardio Pulmonary Investigation unit was formed. Medical Electronics, managed by Neville Martin, being an integral branch of the service. This Cardiac Unit developed to be a centre of excellence, performing procedures on patients from around Australia.

Cardiac Services was the major driver of early Biomedical Equipment.

Over the next 31 years, Neville established the foundation for Biomedical Engineering Services, as we now know it.

In the X-ray Department, the mode of imaging was fluoroscopic. This involved wearing, for long periods, lead aprons and light adjusting goggles. Neville has said he would have felt at home with Darth Vader.

Cardiologists and Cardiac Surgeons were returning from overseas and bringing the latest knowledge, expertise and —- equipment requests. Neville’s support and quick uptake of complex electronic design principles enabled Royal Adelaide Hospital to remain at the forefront of Cardiac Services.

Alterations to Thoracic Theatre were implemented to accommodate heart-lung bypass surgery.

The remote monitoring equipment was housed in a 6-foot high rack and connected via concealed wiring in the ceiling space to the theatre.

Neville has told of how he and Neil Pressley, the Heart Lung Technician, crawled through the roof-space to install the specialised cabling themselves. Considering that both were tall and broad shouldered one can appreciate the challenges.

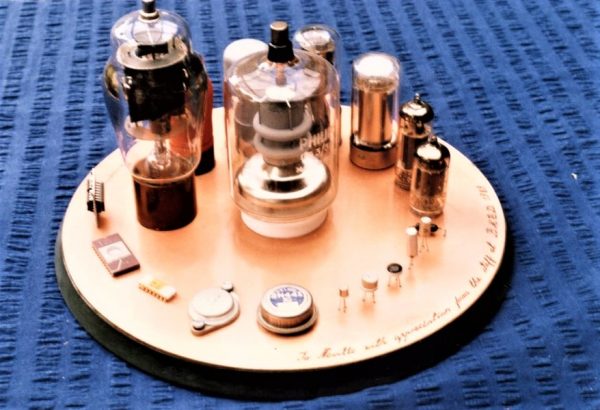

The equipment was designed around radio valve technology. It was necessary for a technician to arrive early to calibrate the rack of monitoring equipment and remain in theatre for the duration of the surgery, being 6-8 hours.

In late 1960’s, the upsurge of electronic devices meant that the Department of Medical Electronics became an identity in itself, with a staff of four. The initial four-bed bay of the late 1960s in Ritchie Annexe with monitors of dressing trolleys, gave way to the purpose-built unit in the New North Wing. Then upgrades to the remote monitoring systems in the Cardiac wards of the East Wing soon followed.

Increasingly, more sophisticated electronic equipment proliferated and it became evident to Neville that significantly more staff would be required.

In 1969, Robert Wiseman become the first school leaver trainee that Neville’s wife, Margaret refers to as “Neville’s Boys”. Over the next decade or so an additional trainee was taken on each year. When Neville retired in 1989, the BME Department had grown to 40 plus staff.

The evolution of technology, such as implantable pacemakers and infusion pumps meant we Biomed’s, were increasingly visible in clinical support roles.

Neville was at the forefront of exponential changes in medical technology and took us along for the ride.

These years were truly exciting and trail-blazing.

The ever-changing technologies and challenges have kept Neville’s team employed, interested and flourishing for the best part of 60 years.

Robert Wiseman has left me with these final words which I am certain all of “Neville’s Boys” would endorse:

Neville was a great mentor, friend and true gentleman who taught me my craft in Biomedical Engineering.