Australian Surgical Teams in South Vietnam, South Australian Staff, presentation to the South Australian Fellows of the Royal Australian College of Surgeons (RACS) c 1967

[transcript of the presentation by Dr C. G. [Graham] Wilson]

I will first of all try to describe for you the Bien Hoa Provincial Hospital in which the South Australian Team worked. I hope this may be of some interest and also the facilities available to us helped to determine much of what we did and how it was done.

The Pham Huu Chi Hospital was named after one of the first Vietnamese doctors to be trained in Western medicine. He trained in Paris with distinction and is said to have been offered a professorship there. He declined this post however to return to Vietnam – an example which could well be followed by many of his colleagues today. There is no record that he ever worked in Bien Hoa, but his name was given to the hospital when it was taken over from the French.

The hospital is built in a rambling pavilion style. Most of the buildings date from 1939 and are of solid construction. However, damp and mildew have stained the walls, rotted the insect screenings and fretted the tiling. Most plumbing in Vietnam is based on the premise that water runs uphill and that in the hospital was no exception.

However, as the water supply, except in the theatre suite, was erratic and scanty any strictures or inadvertent valves in the outlet system were less important.

The sewerage arrangements round the hospital were mysterious and not too savoury and I’m afraid I didn’t investigate them too closely for fear of what I might find.

The kitchen was like an illustration from one of the early editions of Dante’s Inferno. It was frequented by the hospital dogs, a stray cat or so, and some well-developed rats.

The kitchen was like an illustration from one of the early editions of Dante’s Inferno. It was frequented by the hospital dogs, a stray cat or so, and some well-developed rats. Despite this, it provided 2 hot meals daily for 320 patients and their relatives, and although there were certainly odd cases of typhoid and dysentery around there really didn’t seem to be any great problem with gastro-intestinal infections within the hospital.

We had a large 60k.v. auxiliary generator capable of running the theatre suite and the x-ray machine. This was not infrequently in use when the town power supply failed. Unfortunately on at least two occasions when the generator was needed the mechanic had removed the starting batteries for recharging, but had not bothered to tell anyone about it. After this we bought two powerful battery lanterns which we took down at night so that we could at least finish an operation if the town power failed and the generator refused to start.

The hospital had a reasonable x-ray machine – a 100 m.a. machine in the x-ray room and a 15 m.a. portable. Our own radiographer John Quirk, and two Vietnamese nurse radiographers were able to provide a 24 hour service. Apart from plain films we could also do some contrast radiography, pyelograms, choledochograms and sino grams, but barium meals and enemas were not satisfactory as there was no fluoroscopy equipment nor did we have a radiologist.

I mention the laundry because its deficiencies were of considerable importance to us. All hospital linen, sheets, towels, nurses clothes, theatre gowns and so on were washed in two large cement tubs by hand and foot. Even with many willing feet the output was low and we never had enough linen to provide full sterile drapes for other than major cases – even if the autoclave could have put more through.

We used unsterile paper towels for many minor cases including some wound excisions and abscesses or perhaps a paper towel with one small sterile towel under the main wound. For the same reason we used gowns only for major cases though gloves were used for all cases.

The laboratory service in the hospital itself was limited though Peter Last was able to get it going more actively. They could do blood and urine and faeces examinations, direct smear for organisms and blood smears for malaria. We did manage to get cultures done for determination of bacterial sensitivity and we were also able to group and cross match blood. Most of our blood was Group O Rh Positive low titre which we were able to get from the Americans. This was used unmatched and caused surprisingly little trouble – certainly we had no serious incompatibility reactions though the blood if old would not always run well and large transfusions seemed to give rise to a bleeding tendency.

We were able to get the tissue examined histologically at one of the nearly American hospitals and we could get the result in about two weeks.

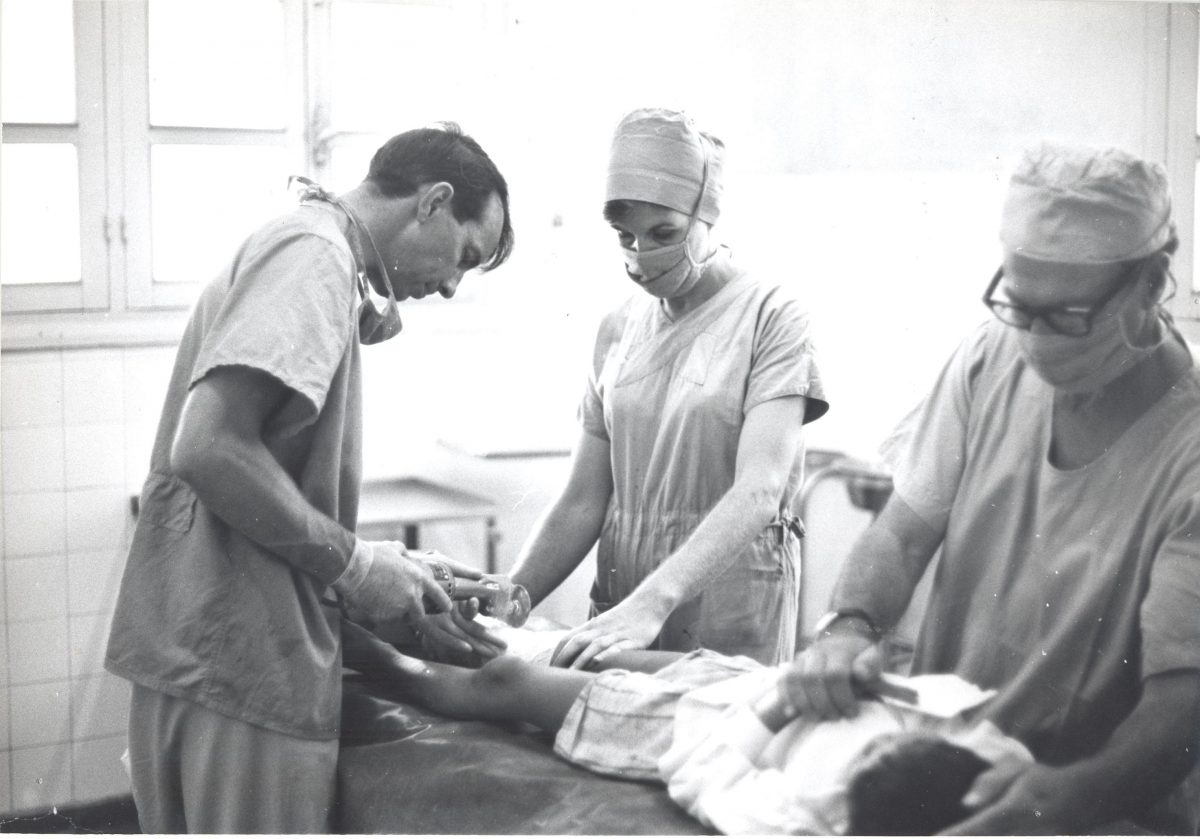

Apart from our own anaesthetists, John Barker and later Tom Allen, there were two Vietnamese nurse anaesthetists and two trainees. The standard anaesthetic was a Pentothal induction followed by the use of an air or oxygen and ether mixture supplemented by Halothane given by an E.M.I. machine with an open circuit. The nurse anaesthetist used relaxants if necessary and could intubate quite well. In fact they gave quite good anaesthetics for all except the most complicated cases. One of them had the habit of arriving late and was often quite difficult to find at night. He had such an engaging manner however, and always got in first with such a cheerful if implausible excuse that it was impossible to get too angry – especially in French.

The Surgical suite itself was built in 1963 to a standard pattern seen throughout South Vietnam. It contained a reception area – two small but adequate theatres and a small scrub up area. There was a rather cramped storage and sterilizing area and a small recovery ward. The two theatres and the recovery ward had air conditioners which worked for some of the time at any rate.

These facilities would have been quite adequate if we had had perhaps 200 cases a month. We averaged over 500 cases a month and they were strained to bursting point. To make some comparison perhaps I can say that McEwin Theatres, including the general, orthopaedic and cystoscopic suites average about 750 cases a month. Our small setup was literally running hot in more ways than one. We inevitably had to make some short cuts which would not be acceptable in a more sophisticated environment. In fact these various short cuts caused less trouble than might have been expected.

It is interesting that this is really the same method as that used in the big operating sessions at the Mayo Clinic. I suspect that we should at least try it at the R.A.H & Q.E.H.

I have already mentioned the linen shortage and inadequate drapes were, I think, our biggest problem. Standard instrument trays – i.e. a laparotomy, craniotomy, thoracotomy and a major wound tray were autoclaved and wrapped ready for use. In addition there were extra instruments, bowel clamps, bone nibblers which were kept in separate sterile wraps and both available to supplement any of the standard trays. This method worked well and greatly reduced the work for the theatre sisters. It is interesting that this is really the same method as that used in the big operating sessions at the Mayo Clinic. I suspect that we should at least try it at the R.A.H & Q.E.H.

Instruments for minor cases, suture of facial lacerations, opening abscesses and so on were simply cleaned and put back in alcohol until they were used again. I’m sure Kevin Anderson would never countenance this method of sterilization, but it was the only way we could cope with the number of our minor cases and in fact seemed to work fairly well.

Our elective cases did not often get infected and we did not really seem to have much more trouble with infection in the war wounds than the Americans did with a much more sophisticated set up. I do not think we had a single burst abdomen in the whole six months – probably because the patients were all thin and tended to lie like logs after operations anyhow. For some reason this did not appear to cause any cases of venous thrombosis – perhaps their serum protein levels were low enough to discourage clotting.

The recovery ward opened off the reception area and contained 7 beds for the most seriously ill patients, and there was usually a sick baby in a cot at one end with one or two children on a barouche in the corner.

On the floor would be up to 8 stretchers with patients who were recovering from their anaesthetics. The recovery ward was looked after by our own ward sisters during the day. One of them would come down in the evening to settle their patients down and after that there was a Vietnamese nurse on duty at night.

A direct line army signals ‘phone connected the surgical suite to our quarters and whoever was on duty would have the ‘phone in his room. The interpreter on duty would ring either about a new patient or because of some trouble in the ward. The opening sentence was usually the crucial one, – “there is a patient” usually meant surgical trouble, but if he said “There is a baby” then there was a sporting chance that we would be able to get the physician on the job. If a patient was reported a tired he was usually pretty sick – if he was very tired you had to hurry or not go at all.

Apart from the recovery ward we managed the mens’ and womens’ surgical wards, the military, the orthopaedic, children’s ward and the private wards. In this last the patients paid 100 piastres a day – about 80 cents Australian for a little more privacy – 6 bed wards with one hand basin per ward but there were no private medical fees involved – or not to us at any rate.

The mens’ and womens’ surgical wards had some 30 to 40 or 50 patients on beds or stretchers in a pretty crowded condition. During our stay there most of the wards finally got sheets for their beds, but the laundry was a bottle neck here.

When you first saw the wards you doubted whether anything could be done there with any degree of sterility at all. In fact they did wound dressings, burns dressings etc. quite well and infection was not the problem that I for one had anticipated.

There are very few trained nurses in Vietnam. They come in three grades – the professional nurse, male and female who have done a 3 or 4 year training in Saigon – an intermediate grade who had a shorter training period and the district trained nurses who had trained in peripheral hospitals.

The Vietnamese nurses would give pills and injections – take temperatures and so on quite adequately. They would do dressings fairly well considering the limited facilities available – there was only one hand basin in each ward with no hot water. However, they would not get a bedpan, make the bed or bring breakfast – that was the families’ job. In fact the devotion within the family group was striking and touching, and to some extent made up for their lack of trained skill. A mother would hold her child’s arm still at night to make sure that the intravenous drip remained open; on the other hand she often did not appreciate the importance of the rate at which the drip was running – on the basis that it you need something then twice as much is twice as good for you, she would let the fluid run in cheerfully throughout the night and get the nurse to provide another flask to keep the drip going. I am sure we lost a few children from overhydration in this way and certainly we had no efficient check on how much intravenous fluid had been given. Orders for I.V. fluids the next day had to be made on a purely clinical basis. I found the clinical assessment of tissue turgor on the dorsum of the had perhaps the most useful sign for this purpose.

The relatives were all over the place. Though it was possible to turf them out while one went round the ward, they would usually still be peering through doors and windows. We soon came to accept this crowd however, and we had to take particular notice of any patient without relatives as it was only too likely that he would receive little food or attention.

As there were only 2 trained nurses on for the whole hospital at night and during siesta (midday till 2.30p.m.) the whole care of the patient devolved on the relatives during these periods. I have already mentioned the trouble this caused with intravenous drips and it produced other problems too. There would be no bladder washouts – so you left a suprapubic tube in as well as a urethral catheter, Ryles tubes would not be aspirated and we never did get the old fashioned Wanensteen apparatus to work. In fact we found that if a Ryles tube was left to drain into a plastic bag – usually the plastic cover of a used drip set – it would continue to drain fairly adequately during the night from intra-abdominal pressure and aspiration could be recommenced if necessary the next morning.

Management of a tracheostomy at night was also unsatisfactory as aspiration would not be done with any sterile precautions and this caused troublesome chest infections in these patients.

Perhaps the most dangerous situation at night was with an unconscious patient. It was difficult to persuade the relatives to keep the patient on his side, and if he vomited we had only one suction in the recovery ward and naturally enough the relatives were not able to use this effectively. In consequence we lost several head injuries from aspiration of vomit and subsequent pneumonia. It may fairly be asked why we did not transfer all such cases. In fact we did transfer some, but we soon saw that the larger Vietnamese hospitals in Saigon had essentially the same trouble as we did and we mostly transferred only those patients, such a s recent paraplegics, whose proper care involved so much nursing attention that to attempt it would have prejudiced what we could do for others.

Once a week a member of the team lectured at the Cho Ray Hospital – this lecture being translated into French by Professor Chieu, Professor of Neurosurgery. I doubt if these lectures were of much use in themselves but the contact with the teaching set up was entirely useful and in the last month we were there we had some final year students, interns with us who lived with us and worked with us at the hospital. This was interesting and valuable and I think it will be expanded with the subsequent teams.

We visited the Leprosarium of Bien San once a fortnight to do some surgery there. This was fascinating as it involved a chopper ride – about 15 minutes and for most us it was our first sight of leprosy. The hospital itself is quite unusual in Vietnam in that it is quiet and clean and there are very few relatives there for obvious reasons. It is run by a few Nuns and a highly extroverted priest who is obviously made for the job and keeps a few bottles of whisky, brandy and beer for his visitor. Most of the work of building the hospital has been done by the lepers themselves – unfortunately the Nuns do not seem to have realized that the anaesthetic fingers and toes of these patients are very susceptible to damage and manual work often precipitates further loss of fingers. By the same token, plantar ulcers need bed rest to heal. This leprosarium badly needs regular frequent visits by an expert in leprosy. As it was we really only did salvage surgery – amputations, excision of metatarsal heads to relieve pressure, and so on. Nevertheless it was always an enjoyable trip, but we felt that much more could have been done if we had been able to devote more to it.

War injuries accounted for over a quarter of our Theatre cases. Over the six month we had 142 major and 757 minor was cases through the theatre – 899 cases in all – about 450 patients as most of these folk appeared twice in theatre, once for their primary wound excision and again 4 or 5 days later for delayed primary closure or skin graft.

This number compares with the 220 Australian battle casualties treated at the Australian Field Ambulance or at U.S. 36th Evacuation Hospital over the 18 months from June 1965 to December 1966. Their mortality reported in the last issue of the Medical Journal of Australia was 2.7% which was slightly lower than ours (3.1%) probably mainly because of the better nursing facilities in the Army Hospitals.

Both figures are comparable with those achieved in Korea (2.4%) and are significantly lower than World War II figures (about 5%). This is largely due I believe to the rapid evacuation of casualties by helicopter. This enables many men to survive who would have died with any other form of evacuation – this includes particularly patients with major haemorrhage. I saw one patient in an American Hospital who survived division of the first part of his left subclavian artery. He reached the hospital within 20 minutes of wounding.

I hope that before too long we may see helicopter evacuation used for the evacuation of civilian casualties in the 20-40mile range from major centres.

The war injuries tended to arrive in batches of three or four, sometimes as many as 16 at a time. At these times one literally hopped between the stretchers in our small reception area.

The initial assessment was vital in deciding which patient should be treated first – who needed resuscitation – which x-rays were needed. We found that is was highly desirable to x-ray all missile wounds before primary excision if large foreign bodies or even complete bullets were not to be left behind. Fortunately the radiographers were able to provide the 24 hour service required. It was important to recognise major nerve or vascular damage prior to operation as it was difficult to define nerves in the middle of an extensive oozing wound.

It was tempting to use a tourniquet at times but this made the distinction between viable and non-viable tissue difficult, though I did use one for some hand wounds.

We soon learnt for ourselves what has been said so often before, that small skin wound often led to extensive deeper damage especially if the missile had struck bone. Even small grenade fragments often penetrated a surprising distance and almost always entered the deep fascia causing significant muscle damage.

This small fragment from a mortar entered in the left side of the back, traversed the sacrospinalis, two loops of jejunum and finished in the sigmoid colon. Following closure of the jejunal holes and exteriorization of the sigmoid injury as a colostomy, the patient did well and left hospital after closure of his colostomy a month later. We tried to sacrifice as little skin as possible, but it was necessary to make long incisions in order to explore the whole wound and excise all dead muscle and as many foreign bodies as possible. Only by fairly ruthless primary excision could we produce a wound clean enough for early delayed primary closure. All patients were give 1500 units A.T.S. and most had penicillin 1,000,000 units b.d. post-operatively.

Our management of abdominal wounds was conventional in that we exteriorized left sided colonic wounds as colostomies. We usually closed or resected wounds of the right colon as well as small bowel injuries, as we thought it unlikely that the patient would survive the fluid and electrolyte loss associated with a ileostomy or colostomy of the ascending colon.

There seemed to be considerable advantages in the early internal fixation of compound fractures of the humerus and femur due to gunshot wounds, especially when as was usually the case, there were other associated injuries. These operations mostly using (Ru)pins or Kuntschner nails were nearly all done by Brian Cornish and Rod White and I won’t discuss this further, but we were all convinced that they were worthwhile in aiding good soft tissue healing even if the pin or nail had to be removed later.

(Slides for illustration associated with this presentation are not available at this point to include in the content of Dr Smith’s lecture.)

The high proportion of wounds of the lower limbs and abdomen reflects the fact that many of these injuries were caused by explosions of grenades, mortar and mines when the fragments essentially came upward from ground level. It also indicates the high mortality of abdominal wounds – especially those causing liver injuries with major haemorrhage.

We only had one case of gas-gangrene following a war injury. This man developed a thrombosis of his femoral artery 48 hours after injury and developed gas-gangrene in wounds of his calf. He survived after an above knee amputation.

Apart from the war injuries we had many patients with diseases or injuries with which we are all familiar here. Traffic accidents were frequent and followed the usual pattern. We saw a number of unusual tropical diseases.

I think we all gained a lot from our time in Vietnam. Certainly, we all found it a fascinating and rewarding time which we would not have missed for anything.